THE FROGS

At first she doesn’t know what to do with herself. She has five loads from the car. A ridiculous excess. Pasta and dairy. Tuna, sardines, anchovies. A whole massive chicken, salmon fillets, two packs of smoked mackerel, Imagine portabella broth, a squat edifice of Trader Joe’s pizzas: woodfired heirloom tomato and arugula. First time in her life she’s been a hoarder. Her liquid provisions: ten bottles of Whole Foods Italian water, a six-pack of Chateauneuf du Pape from Vince’s cellar. Sauvignon Blanc, Tavel Rosé, Hendricks and Stoli for the freezer. Sake. Campari. Cinzano. Glenfiddich, and Courvoisier. She decided against rum—it goes down too easily. If the virus doesn’t get her she’ll drown herself in booze à la Nicholas Cage.

Clearly, she’s going to run out of toilet paper in two weeks unless she changes her habits. That’s what this is about. Retooling the middle-aged brain. Stop touching your face. Wash your hands for long enough to sing Happy Birthday twice. Beam disinfectant vibes wherever you tread. Be mindful.

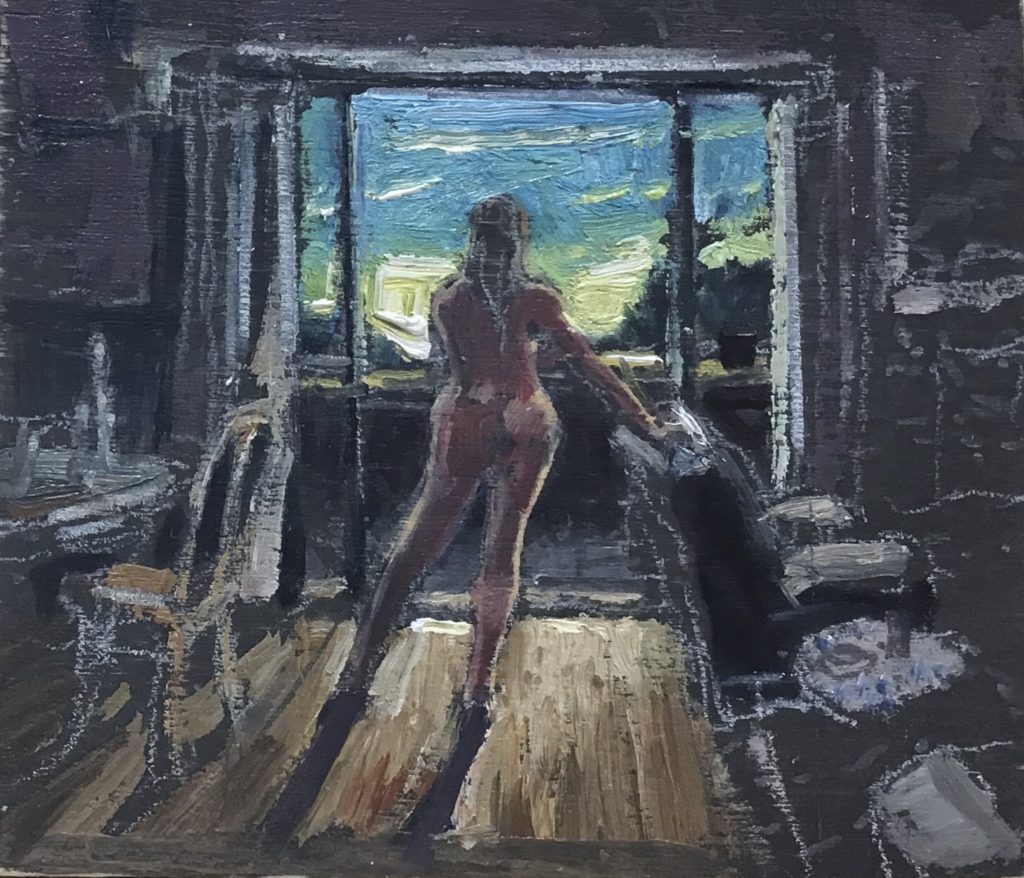

As she puts away the groceries she catches herself picking her nose. There’s no hope for her. Her thoughts come in fragments, bullet points in search of focus. She tries to get herself to sit down a minute, but she’s too wired for that and keeps circling the living room, pausing from time to time in front of Vince’s picture window. That’s what he calls it even though it’s an inelegant sliding glass from the seventies, framed in steel, which nobody can keep clean.

Across the street is a small farm, dense with fava beans that will soon be plowed under to nourish the earth. Every year she’s impressed that this farm, The Patch, refrains from early spring planting. Land stewardship. The phrase pops into her head from who knows where. It’s never been part of her vocabulary.

She heads out to the deck to light a joint and a flash rainstorm with tings of light hail delights her. At the edge of the overhang she gets a little wet. Five hits of Golden Uni and she’s seeing things more clearly. She has options. She pours herself a sake on ice.

This is Vince’s condo with his things and his esthetic: a determinedly male sense of comfort with a wide Italian leather sofa and a pair of Prairie School black leather Morris chairs, not to mention a high-end La-Z-Boy in the second bedroom in front of the TV. Dominating the master bedroom are three charcoal sketches of female nudes by the North Beach artist Homer Sconce, who sold them, Vince claims, for a song.

Although she’s come up with him weekends for seven years, she’s never come alone. Now she’s to stay for the duration. A few years ago three girlfriends from college joined her here for a getaway weekend in June. They hired a limo and went to a few wineries. Molly, the financial advisor with Ameritrade, vomited, mostly out the window, and the others cheered as if it were a midlife triumph. They had more wine with dinner. Olga, the yoga teacher with a bothersome lisp, brought outsized T-bone steaks. She’d thought Olga had become a vegan.

They grilled on the deck. When she saw the slabs of meat on the platter, charred crisp at the fat edges and swimming in blood, she wondered why they were masquerading as men, and as if to amplify this curiosity, Janice, the dentist from Alameda, brought her computer to the table, before they’d even cleared the dinner dishes, and went directly to Porn Hub.

They gathered around the screen amid the detritus of plates heaped with gristle and bone and puddles of blood, and gawked at random cocks. The men attached to them either looked like pea-brained adolescents or heavily-inked carnies who’d just as soon slit your throat as fuck you.

She broke away from the others and stood with a glass of Zinfandel at the picture window. Despite it being dark she knew she was gazing in the direction of rows and rows of Early Girl tomatoes.

At the dining room table, Janice hooted, “I’d take an itty bit of him,” and Molly, who’d fully recovered and was far along on round two, shouted, “You don’t get an itty bit. You get all of him.” It wasn’t the weekend she hoped for.

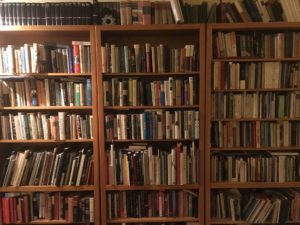

Vince bought the condo after his first wife died and he lived here awhile with his second. He has his library here—a lot of man novels and poetry. He keeps his nonfiction at the house in the city. The poetry was one of the first things that endeared her to him. He’d written it in college but the writing fell away during med school. “Poetry takes time,” he’d said, “and I didn’t have it.” In any case, he’s bought plenty of poetry books over the years and is proud of his collection.

Some nights Vince picks a book off the shelf and reads a poem to her. He’s quite a performer. She wonders if that comes to every man who knows that he’s handsome. His elevated elocution isn’t particularly pretentious. It’s clear he loves the language. The rounded vowels resound with a warm, woody, clarinet timbre.

Her father recited her poems when she was young. Longfellow and Wordsworth, poems he’d learned in school. He loved Whitman’s “O Captain, My Captain.” The poems weren’t delivered as fluidly as Vince’s but he was her father and he was sweet to her. She loved the way his brow furrowed when he tried to remember lines.

She’s never mentioned her father’s affinity with poetry to Vince. In this and in other matters she’s done her best to keep the two men apart, as if standing with arms outstretched, one on each side of her. She’s not been as mindful of this separation with other men, but then Vince is nearly twenty years her senior. It’s her father, who died when she was thirteen, who’s in need of protection. His spirit must endure no matter what becomes of Vince.

A few weeks after they met, he read a poem to her the first time. It was “The Song of Wandering Aengus,” by W. B. Yeats. Later she memorized the poem and began to use the first stanza in her work with a few clients, because it was so lucid and the words fell directly into their natural pockets.

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

That first time, after he’d finished reading the poem, she swallowed some air in the spell of the poem’s simple majesty. She was slayed by its pictorial clarity, not to mention the loveliness of the man reading it. But then he broke his spell, “You know,” he said, “it’s quite daunting to read poetry to a speech pathologist. I imagine you listening to every word with your speech pathologist ears.”

That struck her as an odd thing to say, perhaps because that wasn’t at all the way she’d listened to the poem. “It shouldn’t be daunting,” she said, “to read poetry to the woman you love.”

Their eyes met. She’d clearly overstepped her bounds. Neither of them had yet spoken of love.

At the picture window she’s waiting for dusk. With it, she expects the frogs. It’s been raining. They’ll be out in force and will become her closest confidants.

The first time they came to Sonoma, Vince showed her his beautiful four-volume set of Haiku poems, edited with pithy explication by a divine Englishman, R. H. Blythe. She latched onto the volumes, perhaps as a way of latching on to Vince. And yet, apart from him, the bite-size poems continue to nourish her. She writes them down by the dozens in her daybooks. In Blythe’s volumes the haiku are not translated in the nifty 5-7-5 syllable count that she was taught as a child. When she asked Vince about that he said, “The syllable count is the thing Americans like most about them. They think they’re crossword puzzles or some damn thing.”

Blythe is a sweet companion. He provides context for seeing the burnished images in relief, along with a hint of their spirituality. She brought the four volumes with her to the city and now back to Sonoma. Her favorite poet is Issa. He’s the earthiest. According to Blythe, Issa wrote nearly 300 haikus about frogs.

Frogs squatting this way,

Frogs squatting that way, but all

Cousins or second cousins.

It was Vince’s idea that she isolate up here. Her history of asthma, he argued, put her in the high-risk category. His age marked him as high-risk as well, but he’d stay on the front lines at Kaiser and probably get the virus and probably die. She’s never been especially fatalistic, but now it’s clear that one of her pastimes during the plague will be noting each of her atypical attitudes and behaviors.

The first discussion of isolation was at the dinner table in the city. She’d roasted a leg of lamb in mustard sauce and steamed asparagus that she dashed with olive oil and Balsamic and flecked with red peppers. There’d be plenty of leftover lamb for him to take sandwiches to work. Her office had just closed; she wouldn’t need sandwiches. Vince went at the lamb like it was his last meal and extolled the virtues of the bottle of Oregon Pinot Noir they were sharing. “It’s perfect with the lamb,” he said, “no need for a jammy California Pinot,” and then, very matter of fact, after taking a long sip of wine, he said, “I think you should isolate in Sonoma, Pina.”

“Why not just stay here?”

“You need to isolate from me, darling. I have to keep working.”

The idea shocked her. Her mind whizzed with questions. Was he just trying to get rid of her? Seeing somebody else again? Was this the beginning of the end?

She fixed her eyes on him. “So I’m going to just be left up there like The Woman in the Dunes?” She had no idea where that came from; she hadn’t seen the film in decades and all she remembered was a slight woman with a broom sweeping furiously at the encroaching sands.

“Pina,” he joked, “there are no dunes in Sonoma and very little sand.”

“That’s not what I’m fucking talking about,” she hollered.

He took her hands and nodded, and nodded some more, horse-like. Then, in his let’s-be-reasonable voice, he said, “I can’t have you getting sick. You mean too much to me, Pina.”

This evening, before the frogs start up, she hears the woman downstairs crying. Talking on the phone and crying. Pina’s never met her—a newcomer to the complex—she doesn’t even know her name, but she’s been impressed, the couple of times she seen her, with her fastidiously-coifed wedge of white hair. It matches up surprisingly well with her REI ware.

To cover the sound of the poor woman’s crying, she clicks on Vince’s Bose system, with his thousand imported songs, mostly jazz and a couple of Dylan albums, and keeps clicking forward till she lands on a Bill Evans album she can stand. She’s never met a man so jazz crazed. He accepted, he said, the fact that she didn’t hear jazz. She heard it fine; she just didn’t like it for the most part. It sounded automotive to her, all pistons and thrust, aching for a muffler. That impression may have been gained in part from one of the half dozen framed album covers Vince has on the walls of the living room. It comes from the one that she didn’t understand. She acknowledged the beauty of the others: Coltrane pensive on the cover of Blue Train, Monk honky-tonking at the piano in a funny hat, Dexter Gordon, illusory, shrouded in smoke from the same cigarette forever. But this one: a racing car, a Corvette in motion, titled “Hard Driving Jazz,” made no sense to her. It didn’t align with Vince’s style. A college friend had given him the album. “The dumb fuck,” Vince explained, “thought he’d picked up this cool album to play when he had girls over, but it turned out to be this hot out-there deal with Cecil Taylor on piano and Trane, who for contractual reasons, is listed as Blue Train. Yes, she’d been schooled on the album and, yes, jazz will always sound automotive to her.

Back to what to do with herself, Pina decides to check what’s on TV, and then remembers that last month Vince cancelled the cable service and cancelled the Internet in Sonoma, since they rarely use it. He railed for a half an hour against Comcast. “Why pay those bastards $150 a month?” She still has her phone for the Internet and there’s radio on the Bose system. Clearly she is better off than the Woman in the Dunes. After washing her hands for the tenth time today, despite being in contact with nobody but herself, she wonders exactly who’s birthday it is.

At the picture window, she takes half a gulp of cognac. Vince tells her, you should chew a good cognac. Who wants to chew it? She loves a splash of something strong and fine that brings a burn to the throat. She’s been good today. She wanted to drink the whole bottle of sake but she only did half. Hey, she made it through the first day.

Pina puts all the lights on. It’s dark outside. The frogs are in full serenade. She sees herself in the glass: sharp Italian nose, doubting eyes, high cheekbones, ruthless, or pretending. She parts her lips, which an ex once dubbed her generous lips. She’d like to paint them now with the rich dusty rose matte she brought with her, but instead she dips into the snifter and caramelizes her nostrils before properly drawing the brandy in, like a bird from a feeder. Now she holds it, her tongue is there, a fortified bubble of dark honey on the palate. She resolves to follow this with strong black coffee and another cognac.

The lit room is visible to the street. Not that she wants to be seen in her isolation. Of course, there’s nobody out there. She slips out of her sweater and then pauses at each button of her blouse. Some insane part of her wants to remember every button she’s ever buttoned or unbuttoned or had unbuttoned. She needs a new bra, but she’s out of it. The truth is, she’s always liked her breasts. Her college boyfriend Cole told her they were well turned and she insisted that only ankles and legs could be well turned. “That’s a lie,” he said, with a breast in each hand. But, always a realist, even at twenty, she pointed out that they’d soon droop and become unturned.

She slips off her skirt. Bright pink panties. Who’s she kidding? Actually, it’s surprising how well her body has kept its shape. She’s not going to turn from the sight of it. Feast your eyes, frogs! There are so many out there, so many little green hoboes, such a crowd. What do they know about separation?

It is with deep sadness that we note the passing of former Sonoma County Poet Laureate, Mike Tuggle. As a poet, a mentor, and a friend, he touched many of us in the literary community. He will be long remembered and deeply missed.

It is with deep sadness that we note the passing of former Sonoma County Poet Laureate, Mike Tuggle. As a poet, a mentor, and a friend, he touched many of us in the literary community. He will be long remembered and deeply missed.

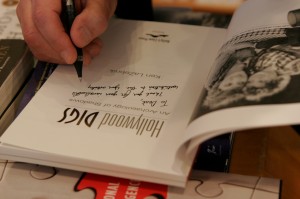

Kelly’s Cove Press is returning to the 2nd Annual

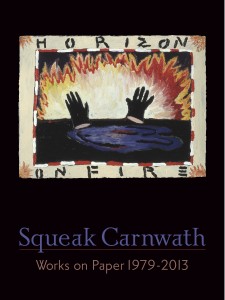

Kelly’s Cove Press is returning to the 2nd Annual  Squeak Carnwath: Works on Paper

Squeak Carnwath: Works on Paper