THE FLY

She wakes early in anticipation of the 6:30 call. Her inner clock is spot-on. Unlike Vince, she never uses an alarm. He likes to hit the snooze button thrice. She doesn’t get it—interrupt your sleep three times for the sake of a few pathetic reprieves.

As she waits for the phone to ring, she thinks of Charlie’s wrestler roar, a mid-range bellow, not exactly Walt Whitman’s “barbaric yawp across the roofs of the world.” Charlie surprised her so marvelously with the wrestling mask that she nearly wet herself. What did he mean by it? Was he expressing his exasperation with her? He admitted, to use her mother’s idiom, having feelings. What does it mean to have feelings you can’t act on? What do risk-free feelings amount to? It’s too much to contemplate with Vince’s voice practically upon her.

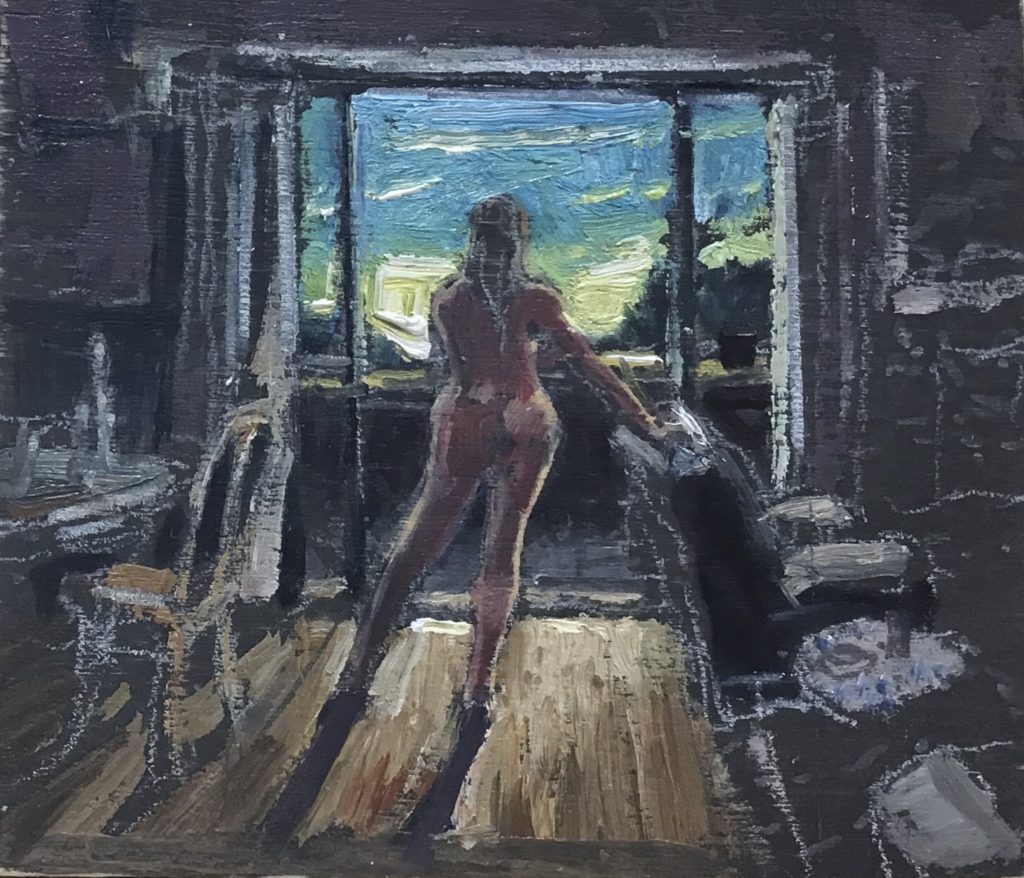

He’s brusque this morning on the phone. He’s starting to freak out. She’s at the window in a light robe, listening and letting him know she’s listening. Everything’s about him. She doesn’t try to distract him, not today, but applies her bare-bones reflexive listening skills: That must be hard, Vince. Oh, I bet that’s scary. He thinks he’s going to die and doesn’t like the idea. He sees it in a very singular way as if others haven’t contemplated the prospect, as well. Of course, he’s on the front line or will soon be. On the other hand, she has her history of asthma. Even though it hasn’t flared in years, her lungs are compromised. If she’s going to die, she’ll die, but she’s not going to waste time worrying about it.

She wonders if Vince would have been a man who fled in battle. She’s ashamed for having the thought, but she persists. What does it mean, to flee a battle, a worthy battle just to spare your own life? Isn’t part of the Hippocratic oath to serve your community, even in times of war and pestilence? Or as Camus’ Dr. Rieux puts it, while contemplating the plague, “The thing is to do your job as it should be done.” Lovely perch she has, above The Patch, for grading other people’s nobility.

“Alright, it’s off to the slaughter yards for me,” Vince says, before signing off, not once asking after her.

Some men burn out quicker than others, she decides in the shower, and some, like her father, die young. The fact is she met Vince too late. He’d already started to wind down. It didn’t stop his philandering. He’d just turned sixty but was ready to bale from his job; he said he’d socked away enough dough. Still vital, he was casting around for hobbies. Playing chess online. Yes, he may have been fond of her, but he was also seeing Pina as his retirement maid.

And if she had met Vince earlier there would have been a lot more hot blood and ugliness. By now she’s sharpened a functional skill, traditionally a male skill, to disassociate. When Vince gets hot she stays cool, so cool that it doesn’t even threaten him.

Once the bathroom mirror is no longer fogged, she stands in front of it for a moment. Pina, Pina, Pina, she says to the reflection of herself. That makes her smile. Her mother used to say, “Smile, Pina, show off those beautiful teeth.” She smiles again, still obedient.

The truth is, she doesn’t know who she is anymore. Maybe she’s never known. Fifty-one-years old and she’s beginning to look worse for wear. Little bags under the eyes, the first sign of vertical wrinkles like slash marks marching across her upper lip, and a suggestion of turkey flesh, beginning to form pleats under her chin. The skin itself has become drier and drier no matter how much moisturizer she lavishes on it. She needs a haircut, that’s for sure. How is she going to accomplish that? First world problem, she thinks, and turns away from the mirror. That nifty phrase, with which the happily privileged gently nudge each other about their advantage, is dated. How do we now differentiate the haves from the have-nots? The solvent and the insolvent? The fed and the unfed? The armed and the unarmed?

She has a new companion this morning: a fly. He, like Vince, wants her undivided attention. But reflexive listening—I hear you, you little buzzer—isn’t as effective as it’s been with Vince. She crosses and re-crosses her legs, flails her arms, but the little guy keeps coming back for more. Rather than trying to swat the fly, she decides she’ll try to better understand it, and picks up the summer volume of Blythe’s Haiku set, where she remembers the fly poems are catalogued. Jackpot. Issa describes the situation perfectly:

One human being

One fly,

In the spacious chamber.

And then he offers a cautionary tale:

Striking the fly,

I hit also

A flowering plant.

Shiki also does the deed:

Killing the fly,

For some time, the small room

Is peaceful.

But Pina decides to leave the domain to the fly and closes herself out on the deck where the bees are active but have no interest in her. She flips open the summer volume to a page where she’s left a marker: “Planting Songs,” a category of its own. Basho has a lovely one:

The beginning of poetry:

The song of the rice-planters,

In the province of Oshu.

And again, Issa:

In the shade of the thicket,

A woman by herself,

Singing the planting song.

Pina imagines a field of women singing planting songs. The same song, not in unison, but in rounds with thin and stout voices, young and old.

Soon they will be planting at The Patch. The few planters here, Latino men, are remarkably efficient. If they sing, she doubts it’s planting songs they’re singing. The Miwok must have planted seeds in this valley. Maize. But what does she know? Nothing about the Miwok, that’s for sure. She goes on a silent rant. Why are we not taught anything about the people whose ancestral land this is? Born and raised in the Bay Area, and we have no curiosity about the first people to live on this land.

Without disturbing the fly, she dashes in to grab her computer, and discovers, on the Angel Island Conservancy site, this pithy profile: “The Miwoks had no pottery, made no fabric, and planted no seeds. They kept no domestic animals. Instead, they were gatherers, fisherman, hunters, and basket makers.”

Pina admires the efficient distillation, in three short sentences, of a way of life, and realizes, sadly, that her thirst for information about the Miwok has been slaked.

Pina walks into town with a ham and cheese sandwich, a baggie of salt and pepper potato chips, celery sticks, and a teeny Tupperware of almond butter, a lunch almost worthy of Albert the badger. She didn’t bring the mango cannabis gummies she set aside for dessert. She’s a truant. It’s already 12:15 and Charlie’s not expecting her. He may have scarfed down his goose liver paté and scrammed. She’s not going to go directly to the white bench. She doesn’t want to look desperate. She’ll loop the square the opposite way. If he’s there when she makes it around, fine.

She scoots south down the east side past Dirty Girl Donuts, which produces glazed profanities in iridescent shades that don’t exist elsewhere in the world.

Despite their bakery exemption, D. G. is shuttered for the duration, but the Basque Boulangerie is still open for take-out.

Charlie’s probably seen her by now, and is watching her loiter, timing her as she makes her way around the square. Is he following now? She doesn’t look back. Charlie is playing with distance. It’s rather thrilling. Is he following her?

She cuts up the alley past the Basque’s cooling racks, sniffing country rounds and sour baguettes. Murphy’s Irish Pub, a ghost of itself with the chairs crooked atop the tables, offers take-out, five evenings a week, beer-battered fish & chips and buttermilk chicken breasts.

The real temptation comes next door at the 1920’s Sebastiani Theatre, which under normal circumstances would be showing “Portrait of a Woman on Fire,” the title hand-lettered above the blue-suited eternal ticket taker. Pina would truly love to break into the theater and flick on the digital projector. If Charlie snuck in and chose one of the lumpy seats two rows behind her, she might become undone. But she keeps going, without glancing back toward Charlie, who surely must be following by now. Past the shuttered Town Pump, the lively tavern that usually has a signboard out front advertising, Daycare for Husbands.

She can’t resist a glance back as she turns onto the south side, but Charlie must be laying low in a storefront. She’s surprised to see a guy, high on a cherry picker, affixing a regal sign to a yet-to-open shop, The Sausage Emporium. Nice that somebody’s feeling bullish about the future. The building blocks of the new Sonoma, reborn beside the old adobes, will be garish-glazed donuts, buttermilk chicken breasts, and artisanal sausages. Surely, all of the winetasting shops—maybe twenty-five around the square and in the alleys—can’t survive.

But Pina expects The Church Mouse thrift shop will thrive. It’s the place that helped Vince get going with his cocktail shaker collection. She stops at the window, which as thrift store windows go, is top drawer. It’s designed to honor the Academy Awards and the Sonoma Film Festival (cancelled). Posters of Marilyn and a few old movie reels flank a woman in a floor-length magenta dress, bejeweled in faux diamonds and a mink stole. Pina keeps expecting Charlie to creep up behind her so that she’ll first see him reflected in the window display. But, no.

She crosses to the park side of the street, where she spots three rapacious mallards resting in the grass. By the time she makes it to the north side of the square, Charlie’s nowhere to be seen. She’s made the whole thing up. Such absurdity. She’s behaving like a prepubescent teenybopper. How can she fall in love with a man she can’t even touch?

She’s reminded of a story Sylvia, a psychotherapist friend told about her daughter Allie, who, at twelve, announced that she was “going out” with a classmate named Alec. “They didn’t go out once,” Sylvia said, “and then a few weeks later Alec broke up with her. Allie’s stoic response, “I guess were not going out anymore.”

Pina sits a moment on the white bench, reaching into her sack for celery sticks. Actually, she has no heart for eating. As she leaves the square she wishes she could hear his call: Pina, Pina, Pina. The silence is not golden.

At home, the fly is also silent. Maybe he made his way out an open window. She pours herself a Campari—a little something to stimulate the appetite—and opens to the second part of The Plague. Nodding along, she reads: “Under other circumstances our townsfolk would probably have found an outlet in increased activity, a more sociable life. But the plague forced inactivity on them, limiting their movements to the same dull round inside the town, and throwing them, day by day, on the illusive solace of their memories.”

Time to refresh her Campari. After another, with a couple of splashes of Hendrick’s and Cinzano, she’ll have the appetite of a horse.

Pina puts her feet up on the ottoman and settles back with The Plague. Her Negroni isn’t quite right; it’s a little on the sweet side. She wonders how two mango gummies will alter the flavor and, as she chews them, the wily fly finds her again. He’s risen from his slumber and his personality, after repose, is friskier than ever.

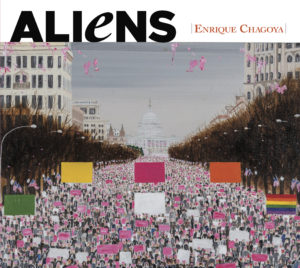

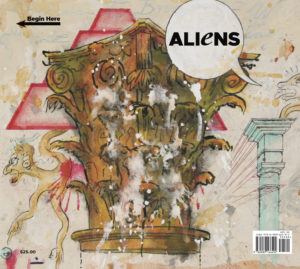

Chagoya’s work, which encompasses drawings, paintings, etchings, lithographs and multi-paneled codices, wrestles with themes of immigration, borderlands, and cultural appropriation, often employing the centuries-old tradition of Mexican cartooning. The artist turns historical narratives about indigenous people on their head in his pioneering work in “Reverse Anthropology” and “Reverse Modernism.” With exquisite craftsmanship, Chagoya has Mickey Mouse and Superman mash-up with Chief Wahoo and Tlaloc, the Aztec rain god. His 2018 etching, “The President’s Xenophobic Nightmare in a Foreign Language,” features Trump’s head on a platter, his pompadour glazed in place, while a circle of savages nibble on his intestines.

Chagoya’s work, which encompasses drawings, paintings, etchings, lithographs and multi-paneled codices, wrestles with themes of immigration, borderlands, and cultural appropriation, often employing the centuries-old tradition of Mexican cartooning. The artist turns historical narratives about indigenous people on their head in his pioneering work in “Reverse Anthropology” and “Reverse Modernism.” With exquisite craftsmanship, Chagoya has Mickey Mouse and Superman mash-up with Chief Wahoo and Tlaloc, the Aztec rain god. His 2018 etching, “The President’s Xenophobic Nightmare in a Foreign Language,” features Trump’s head on a platter, his pompadour glazed in place, while a circle of savages nibble on his intestines. Aliens is divided in halves, one half, proceeding from left to right showcases individual works that fall on a single page; the other half unfolds from right to left, in the traditional manner of codices, and presents twelve codices in their entirety, with sixteen foldout pages for uninterrupted appreciation of the work.

Aliens is divided in halves, one half, proceeding from left to right showcases individual works that fall on a single page; the other half unfolds from right to left, in the traditional manner of codices, and presents twelve codices in their entirety, with sixteen foldout pages for uninterrupted appreciation of the work.