THE BEE

Vince did not call this morning. She’d made an early cup of coffee at 5:30 after going to bed late. He’d been odd when he called at midnight, troubled, and lashing out, not at her but at the civilization. He’s part Old Testament prophet, the voice of doom. That’s where he goes when he feels out of control, ineffectual. And sure, he’s in the middle of it now.

She humored him as well as she could: “Yes, I think the end of the world may be near. I lurked a half an hour on Facebook the other day. Everybody’s putting up vintage photos of themselves, pictures from the first grade and their prom. ‘Oh, you’re so cute, Andrea.’ I think people’s instinct is to make their own memorials.”

“Right. Next they’re going to start posting what they want for their last meal.”

“What would you choose, Vince?”

“Oh, don’t do that to me, Pina. If you knew the garbage I’m eating to get by.”

“Come on, Vince, we’re talking last meal here?”

“Alright, alright. It’s crazy, all I’m craving is fish. I want an endless meal from Cala. Start with the kampachi ceviche, then bring me a dunganess crab tostada, a squid taco in salsa negra, the sopes with smoked lingcod, and a mussel tamale.”

“That’s it?”

“Enough of this nonsense, Pina. Cala’s closed for the duration and the most I can hope for is a fillet-o-fish from McDonald’s.”

The thought of a McDonald’s fish sandwich made her cringe, and she remembered the cheeseburger she made earlier in the evening, a massive patty filled with diced red pepper, broiled to a perfect rare like you can never get in a restaurant, and bathed in Vella pepper-jack cheese with three thick slices of bacon between a toasted caraway seed bun. She ate it all and let the grease drip off her chin onto the plate—heathen that she’s become—before resorting to the serviette. She’s been overwhelmed by an obsession with food since the plague started. It must be a survival instinct kicking in, that and having so much time on her hands. But, clearly, her mantra has become that of the carnivorous plant in “Little Shop of Horrors”: Feed me, feed me.

Now she asks how it’s going at Kaiser and, per usual, Vince changes the subject. Instead he talks about grim stories he’s heard recently on “All Things Considered.” Parents have stopped bringing their children in for necessary vaccinations. “Do you know what that means, Pina?”

“Epidemics of measles,” she ventures.

“Right. And much more.”

Then he pivots to a story about a Kenyan flower grower who had to plow under his whole harvest because nobody’s buying flowers anymore.

She wonders when he finds the time to listen to “All Things Considered.” Do they have the radio on at the hospital?

“Now meat packing plants are closing all over the country.”

“Wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world to become vegetarians.”

“That’s not the point, Pina. Safeway’s distribution center in Tracy is reporting fifty-one cases of Covid-19, which means all the produce coming to Safeway is suspect. The damage to our food chain is absolute, irrevocable, down right nuclear.”

“Then we better start growing a victory garden, Vince.”

“Yeah, right. What are we going to live off of—San Francisco fog tomatoes?”

She glanced out the picture window toward The Patch. “Everything grows in Sonoma.”

“I’ll tell you what it’s going to be like.”

She didn’t want to hear his version. They’d do better going back to phone sex, although she could do without any more of his dick pics.

“Did you ever see that sci-fi film ‘Soylent Green?’ Nice wholesome dystopian flick. The world has run out of natural food so people eat these wafers called Soylent Green. Old people like me are encouraged to be euthanized. Edward G. Robinson, the veteran of gangster films, volunteers. They give him a nice send-off, play Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ as he fades into the ether. The great line in the movie comes when somebody discovers the source of the wafers: ‘Soylent Green is people!’”

“So you think we’re going to be eating Soylent Green, Vince.”

“I think the human race may turn into the Donner Party—the survival of the fittest.”

“Well, that’s good news for me, Vince, because I’m feeling especially fit.”

Vince spit out each word of his response as if he were disgusted with her: “Bully for you, Pina.”

“And I’m going to survive without eating anybody else’s kidneys. Get some sleep, and take care of yourself. I do love you, Vince.” She said the last sentence because she wanted to hear how it would sound. But there was some truth to it. Did she think I love you would serve as a palliative for a man whose nerves are shot?

He didn’t respond, not at first, but finally he mumbled, as if distracted: “Yeah, yeah. Night, Pina.”

She expected he’d at least, sign off with a love you, too.”

Later, after sniffing her cognac for the longest time, she took a mouthful and chewed on it before swallowing. Then she whispered out loud: “Tonight is the end of Pina and Vince.”

She still expected his phone call in the morning. She will continue taking them, and will keep being his faux wife until they reach the far side of the plague. The thing is, she’s already made the separation from Vince. She can feel it in her body. Breathing has become easier. She seriously doubts that she’ll be troubled with seller’s remorse.

So what happened to Vince? Had he gone to bed without setting his snooze? Was he exasperated with her for not sharing his fatalism? Or had he arrived at the same conclusion as her?

Soon as Pina realizes that Vince isn’t calling, she whips up a Bloody Mary. Strong and spicy. That’s how she wants to go through this day. She’s not about to eat a Soylent Green wafer. In fact, she has a lot of goodies in the fridge, enough to make a lunch bag the badger Albert would be proud of. Feed me, feed me.

She’s not sure what to wear. There’s supposed to be a high of seventy today. After concluding jeans would be too casual, she decides on a sleeveless ivory linen dress; she’ll throw her cornflower cashmere sweater over her shoulders in case the wind comes up. Now she sprays a floral perfume on her wrists and her throat. It’s Ylang 49 by Le Labo. She discovered it last spring when she wandered into Macy’s on Union Square looking for a new fragrance. She tried a number of them before settling on this blend of gardenia and ylang ylang. It was ridiculously expensive and she enjoyed making the splurge. Now she realizes she’s sprayed on too much and, unless she takes a shower and starts in all over again, her lingering sillage will be like what a thoroughly-doused woman leaves after departing an elevator. What the hell? She will live dangerously.

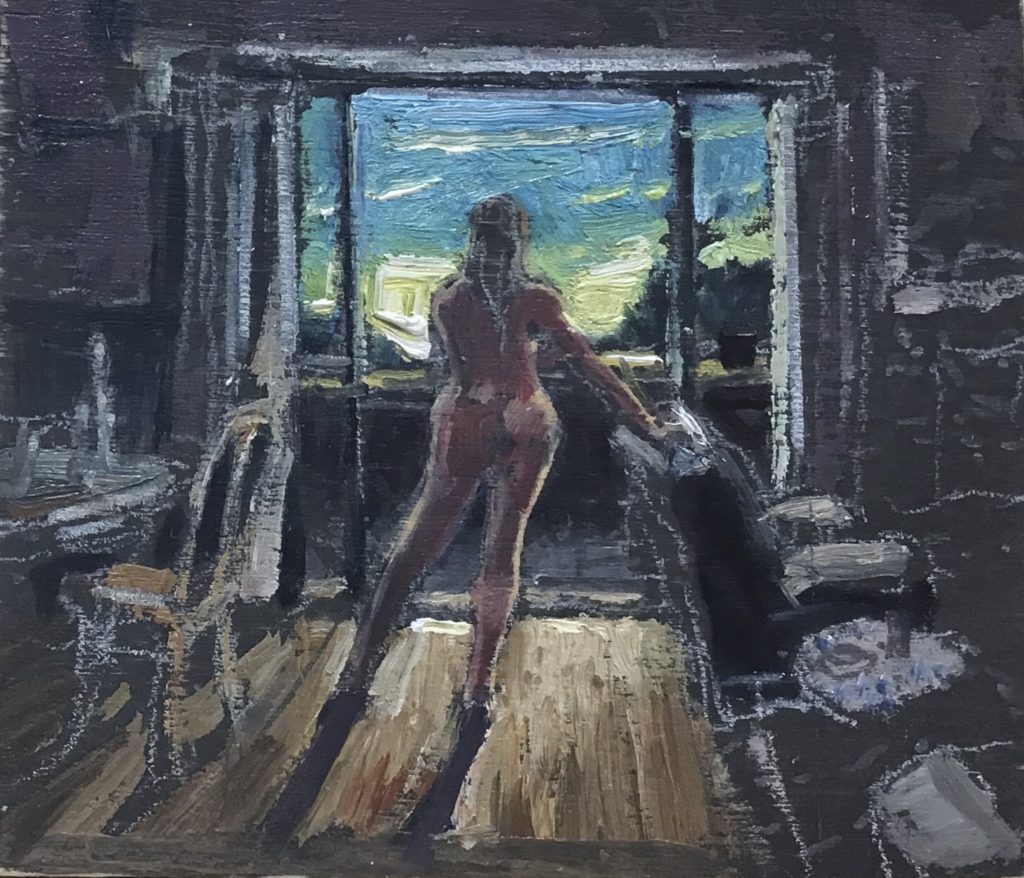

“Pina,” Charlie says, “so nice to see you. Come out on out to the deck.” He walks faster than she wants to go, so she simply pauses in front of three intriguing paintings on the south wall. Each of the square canvases, maybe 16 x 16, feature a gloved hand with a watch timed 6:05 on the wrist above the glove. The first is a rust-hued suede work mitt, with a rough nubby texture that you can practically feel; the middle one is an ebony dress variety with gentle creases that suggest the ultra soft leather might be deerskin; the third picture, painted with more of a cartoonish approach, depicts a fat synthetic glove made for ultra cold weather.

“Those are quite amazing paintings,” she says, as she stands on the deck in front of her appointed chair, a good ten feet from Charlie’s.

“Have a seat, Pina, have a seat. Yes, those are made by my Sonoma buddy Arrow Wilk. He’s got a studio off Lovell Valley Road. Old barn. Wonderful spot. I’ll take you out there some day. Arrow’s a disciple of Philip Guston. You can see it in the fat glove and the timed watches. Maybe ten years ago, I was out at his place and everything on the wall looked like a Guston. I said, ‘Arrow, Arrow, what are you trying to do, out Guston, Philip Guston?’ He goes, ‘Charlie, what can I do? I’m like one of those alto sax guys after Charlie Parker came on the scene—they could care less about their own style; all they wanted to do was sound like Bird.’

“I have several more of Arrow’s paintings in the second bedroom. He’s onto something really cool now. I think he may be capturing the zeitgeist. He’s painting gloved hands scratching masked faces, and calls the series, Hand to Mouth. I’ve been trying to buy a couple off him, but no more people’s prices for Arrow. Say, I have something cold in the fridge for us, if that’s alright. Did you bring a glass, Pina?”

She pulls a little Ikea tumbler from her bag.

“That’ll do.”

She’s a little afraid of Charlie right now, how drawn to him she is. She glances at his impressive row of plants: huge pots of roses just beginning to bloom, and several miniature citrus, also in blossom. Bees, drunk with nectar, swarm the blossoms.

“What kin of citrus are these?” she asks.

“Well, that there is a Mandarin,” he says, pointing to the smallest plant. “It’s yield will be modest, eight or ten fruit, but they’re lovely as they grow and I keep them on there for as long as I can. The next, as you can see, is a striped kumquat with last year’s fruit still on and plenty of fresh blossoms.”

“Those are the hugest kumquats I’ve ever seen.” They seem to grow in pairs and once she sees them as testicles she can’t stop seeing them that way.

“The others are a blood orange that went on strike last year and the prolific meyer lemon. That little plant will give me upwards of forty fruits.”

Charlie stands and with a puckish expression, says, “Boy, I love your fragrance. Floral. I pick up a note of gardenia.”

“Wow, you have a good nose. I accidentally put on too much.”

Charlie nods to her on his way to the kitchen. “Come on, Pina, there are no accidents.”

The way he says that lifts the hair on her arms. All the senses at once, but the scent is too much. Why did she go mad with Ylang 49? What’s the matter with her? Is her thermostat shot? Plus she remembers the saleswoman repeating how long lasting Ylang 49 is. She’s going to have to make a quick getaway or she’ll asphyxiate them both. But Pina only gets up briefly to squeeze a pair of massive kumquats.

Charlie brings out a bottle of Veuve Clicquot and a vintage ice bucket embossed Moet & Chandon. Two champagnes at once, she thinks, and then looks at Charlie, really for the first time as he shimmies the cork out with his thumbs. The two of them are in sync, at least in one way—he, too, wears linen, shorts down fall past his knees. And yet he becomes unquestionably dominant in a weathered polo shirt, a painter’s shirt, you’d think, with wide stripes in uncommon colors: creamy turquoise, chalk with a bit of sand in it, and bruised bronze. On top of that he’s barefoot and has beautiful, long toes. Oh my God, he’s aroused her; just by the virtue of his long toes she wants him.

Charlie produces an identical Ikea tumbler and fills both of their glasses, and lifts his. “I thought that we should toast the fact that we’re both alive.”

“Indeed.”

They air-toast as she squirms a bit in her deck chair. “Poor Vince thinks the end’s near, not the virus but civilization in general.”

Charlie lifts his glass again. “To Vince and the apocalypse! That be a good title for an album. Oh, I shouldn’t jest. Vince is on the front line.”

“He’d do the same.” She drinks her Veuve right down and wants more. Charlie, like Marco before him, doesn’t miss a beat, and now she sips the lovely brut.

“So where’s Roscoe? I though I’d be meeting him.”

“He’s sheltering in place in the second bedroom.”

“With the other Arrow’s?”

“Yes, they’re a series of tongues, unquestionably human. One is dotted with studs like a cloved Christmas ham. Another appears double-jointed, the way it arches back on itself. As you can imagine, Roscoe finds the tongues enchanting. “

Pina wonders what Charlie has hanging in the master bedroom and, just as she has the thought, he says, “Guess what I have up in my bedroom.”

This is getting fucking scary. She should get up right now and leave. “What do you have?”

“Vince’s Mexican wrestling mask collection.”

“What do you mean you have Vince’s . . .”

“Oh, didn’t you know? He sold the collection to me a few years ago. I know I paid too much for them. But what the hell, I love the masks. I guess Vince tired of them.”

“He never had them up. I think he was afraid of them.”

“Hell, they don’t scare me; I find them inspiring! But back to Roscoe. He’s a very intelligent parrot, you know. They’d love to have him at one of the zoos, turn him into an entertainer, but that’s not where his potential lies. I think his future is as a linguist. He has a growing vocabulary of more than 500 words. I play all sorts of recordings for him, human and animal. He loves the soundtrack of “The Lion King” and he does a good Simba. He’s mastered a few accents—the Texas drawl: Hey, y’all; gangster: ya dirty stool pigeon; and French: a tout a l’heure, al-i-ga-tour.”

“He doesn’t say that, Charlie.”

“He does, he really does. He definitely wants to meet you, Pina. Maybe a little later.”

Her head is swirling and she’s hardly had anything to drink.

“So what do you have for lunch today?” Charlie asks.

This is the moment she’s been waiting for. “Funny that you ask. I have a peanut butter and honey sandwich on Mike the baker’s Einkorn mini loaf, a cucumber and onion salad with sour cream and red wine vinegar, and a little bunch of Muscat grapes.”

“How many food miles do those grapes have, Pina?”

“I don’t know, how far is Chile? Are you having any more than bread and jam for lunch, Charlie?”

He refills her glass. “You bet. I’ve fixed myself a Jewish lunch.”

“I didn’t know you were Jewish.”

“I’m not, but I grew up among Jews and I appreciate a largely maligned cuisine. I also hit the discount Passover shelves at Safeway as soon as the holiday waned. I’ve got Gefilte fish and horseradish, matzos with homemade chopped chicken liver, and a kosher l’pesach macaroon. Do you want to trade?”

She shakes her head and pulls out her peanut butter and honey sandwich. Just like that, three bees form the citrus find her and the sandwich. She’s never been phobic about bees and swats casually at them. They flutter off and return.

“Are they bothering you?” Charlie asks.

“It’s nothing.” This time she gives the bees the back of her hand and one manages to stick to her. “Ouch.” Aroused, and smelling like a perfume factory, she’s fucking stung, right here on Charlie’s deck.

“Did he get you?”

She nods. Everything is too much.

“I wish I could help you, Pina, but, you know, the distance thing. Get the stinger out. My mother always rubbed apple cider vinegar on them. You’re not allergic or anything?”

Pina shakes her head. Apple cider vinegar. She stands and forces a smile. “I got to go, Charlie. I got to go.”