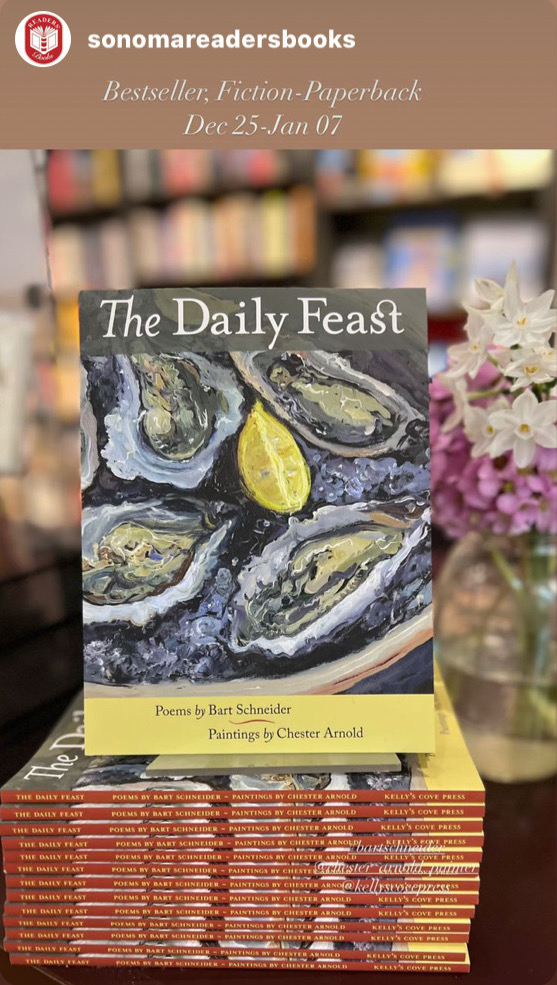

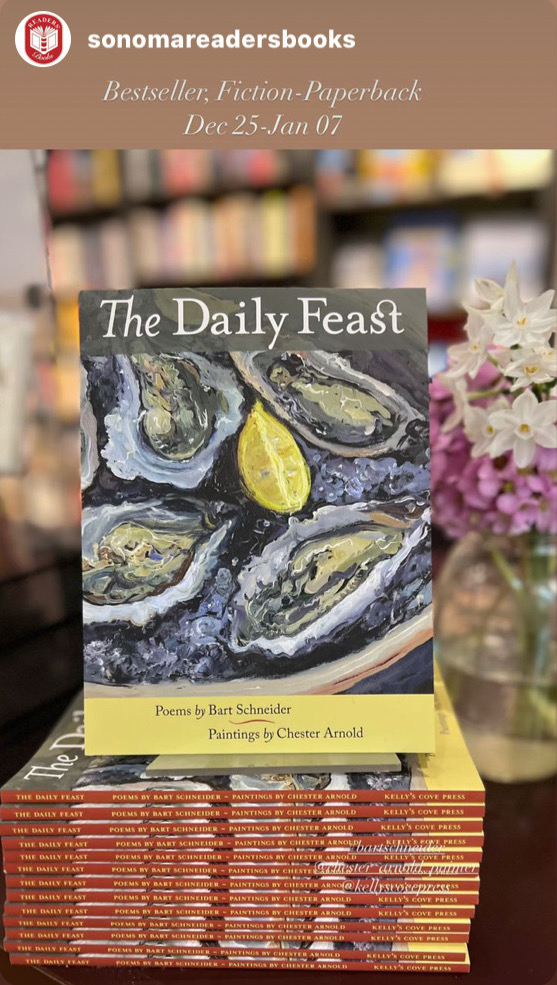

We’re thrilled at the audience reception for The Daily Feast, which won the title of “Bestseller – Fiction – Paperback” at Readers’ Books in December. Thank you Readers’ for your support of our small press!

We’re thrilled at the audience reception for The Daily Feast, which won the title of “Bestseller – Fiction – Paperback” at Readers’ Books in December. Thank you Readers’ for your support of our small press!

I can’t believe what I saw: Vince, who’s just crossed the street, says some shit about the dead rooster killed by the dog, that Gus, here, in the vegetable shed, has been yakking about. I don’t hear the words clearly, but they set Charlie off. He lurches toward Vince, who’s backing up. Doesn’t say a word, but clocks him. The chillest man I’ve ever known floors the most arrogant with a single blow.

My first reaction is exhilaration, I’m ashamed to say, like some honky-tonk chick in a B movie, who’s got two guys going bare-fisted over her. I can see it all from the shed: a large-headed white woman screaming at Charlie as he walks away without a glance toward me, like we didn’t walk over here together to get vegetables; and Vince, on the dusty ground in his striped pants, talking himself into sitting up, beside a couple of fallen breadfruits.

I’m not ready to go out there. I move from the squash to the potatoes and start dropping good-sized russets with dirty faces into my sack. Gus, who, since we met in May, has taken a perverse pleasure in calling me Pita, rather than Pina, has the same idea as I did: “So you got your boyfriends fighting over you, Pita. Nice trick.”

I don’t respond. I keep dropping potatoes into the sack. When I’ve collected about twenty, Gus says, “What’s the deal here, Pita, are you buying all those potatoes or are you playing some kind of counting game?”

Why be offended by a geriatric sot, plopped on his ass ogling and disrespecting me?

“I’m buying them, Gus, unless you have a limit per person on russet potatoes.”

“They’re all yours, Sis.”

I plop more potatoes into my bag.

“So what are you going to do with all those taters?”

“Throw them at men I don’t like.”

“That’s a lot of men.”

“Some guys will get multiple potatoes, Gus.”

“Good thing you like me.”

“I might not waste a potato on you.”

I pile them up on the counter in front of Gus and watch as he struggles to get them all on the small scale, in fours and fives. When a couple of them slide off the scale and hit the ground, he gets all flustered.

I say, “You’re not used to potato-tossing women, are you, Gus?”

“You’re crazy as a loon, Pita.”

Vince is on his feet by the time I haul my twenty-three pounds of potatoes out of the shed. He’s taken off his mask and used it to wipe blood from the corner of his mouth.

“What you got there?” he asks.

I keep walking, taking lurching steps with my heavy load.

“Not getting a whole lot of love from you and Romeo,” Vince calls after me. “Why not come over to my pad and give me a little comfort, Pina?”

“Fat chance.”

“Tell Romeo that he’s got his coming.”

Once I haul the potatoes up the steps I drop them on the concrete landing to make a hearty boom. This brings Charlie to the door with a grin on his face.

“What was that all about?” I ask.

“It wasn’t premeditated.”

“Does that mean whenever the instinct strikes you, you’ll slug somebody?”

Charlie has lost his grin; instead he’s studying me. “Are you coming inside?”

“You done hitting people?”

He gazes down at my sack. “I see you bought a few potatoes.”

“I’m going to make latkes.”

“For the whole neighborhood?”

“I looked up latkes on the Times website; they have twenty-one different recipes.”

“And you’re going to make them all?”

I enjoy that neither of us answers the other. It’s a curious duet, like our relationship—a partita of unanswered questions.

“Is it cultural appropriation,” I ask, “for a gentile to make latkes?”

Charlie pulls the door open wider. That’s as close as he’ll get to truly inviting me in. I’ve made an executive decision: I’m not picking up the potatoes again—twenty-three pounds of brainless spuds plopped there in the cloth sack. I gather the mouth of it and drag the sack, humpty-dump over the threshold, into the hall and then across the wood floor, straight to the brick fireplace. The firewood is stacked, nobly in its rack, on the other side of the gaping black mouth. I spill out the humble potatoes, in twos and threes, and decide to make a small mountain of them. Charlie watches with his mouth open. Does he, like Gus, think I’m crazy as a loon? I stand back from the pile. Seen from a distance it might represent an entire civilization. Some freckled and misshapen, some with random eyes and sharp chins, this pile of brown roots most certainly predates us.

I get a call from Sally, who sounds more than a little bonkers. At least she gets down to business: “We need to do an intervention on my dad, Pina.”

“What’s he done now?” I ask, trying to bring a measure of levity to the conversation.

“This is no time to jest.”

“Who’s jesting?”

“I mean if you’re like in an oppositional state, Pina, I’ll find another ally.”

I hear the revved motor behind Sally’s voice; her mind’s running a mile a minute. “What’s the issue?” I ask in a flat voice that cannot be misconstrued.

“It’s an abdication . . .”

Is the poor girl referring to royalty? Has she just begun watching The Crown?

“A dereliction of duty.”

“What duty?”

“Charlie’s responsibility to Roscoe.”

“Has he not been feeding the parrot?”

“I think you’re purposely being oppositional, Pina.”

If she keeps saying that word I’ll take it as a suggestion. “I am not. Please explain.”

“Charlie has allowed Roscoe to go dormant, missing in action, right when we need him most. The Electoral College electors have confirmed Biden’s victory. Mitch McConnell has congratulated Biden and called on his fellow Repugnants to ditch their fraud conspiracy nonsense; the Georgia senate races are looming; cabinet appointments are being made, and where is Roscoe? We need his pithy statements, his wisdom, his joy. We can’t go on with this radio silence. Charlie has built a brand just at the point of taking off; now is the time to capitalize.”

Capital sounds like the key word. Sally is seeing dollar signs. At the risk of sounding oppositional I ask, “What if Charlie isn’t interested in perusing the brand idea?”

“Then he’s a fool,” his daughter says.

“Shall I relay the message?”

“You’re not useful at all, Pina.”

“Funny, I’ve been told that before.”

The conversation ends abruptly as Sally hangs up on me.

Tonight I make latkes for the second time, box-grating the potatoes in hopes they’ll be less like the Cuisinart-shredded taters of last night, which came out a bit like hash browns. I use Florence Fabricant’s recipe with four eggs and fifteen ounces of ricotta cheese. It makes forty small latkes and Charlie and I manage to eat thirty-one of them. We have apple slices, caramelized marvelously in butter after a slow sauté in Charlie’s copper skillet, and figure with the near-pound of ricotta that we don’t need a side of sour cream.

“As it is,” Charlie says, “our cholesterol readings are off the charts after two nights of latkes.”

“Do you think we can trigger simultaneous heart attacks?” I wonder. “We’d be inventing a new form of double suicide.”

Charlie’s expression turns thoughtful. “Death by latke. Have another one, Pina.”

I comply but when I ask Charlie to join me he demures. “Oh, so you want to watch me die.”

Then Charlie turns grim. He says he thinks we might all die given the way the virus is exploding and how many dumb yahoos in this country are still in COVID denial. “There’s guys on their deathbeds,” Charlie shouts, “unwilling to admit that it’s the virus that’s killing them. They want it to be cancer so bad.”

Charlie trots out numbers: 251,000 cases a day and 3,330 deaths. He tosses his hands in the air, exasperated. “I remember back in the summer, when we had 50,000 cases a day. Dr. Fauci said, ‘If we don’t wear our masks and avoid parties, we may see 100,000 cases a day. That forecast was shocking. Look at us now, we’re two and a half times that, and the Christmas disaster is right ahead.”

Over a salad of little gems and radicchio, with a sharp vinaigrette, I steered the conversation to the merits of each style of latke. Surprisingly we agreed that the first night’s latkes were the superior. “Both crisper,” Charlie says, “and more succulent.”

Next I tell Charlie about my conversation with his daughter.

“I think Sally’s using,” he says, “and I don’t know what to do about it, so I do nothing. That’s what Al-anon would recommend.”

Charlie’s head dips toward the table and I find myself looking at the bald spot in the center of his skull; it’s widened significantly since I’ve known him—the perfect year for a man’s hair to fall out. I reach over and grab Charlie’s hand.

If it weren’t for the virus,” he says, “I might be tempted to get in there and try to help Sally sort things out, and would probably fuck things up further.”

“Well, just so you remember that it’s Sally who wants to do an intervention on you.”

“And you weren’t tempted to help here?”

“Hmm. I might, you know, if you get too deep into the Roscoe branding thing.

Charlie rolls his eyes. “I could give a shit about the branding, but I agree with her that I should be utilizing Roscoe to get certain messages across—I’m just not sure what the messages are.”

I have nothing to add and, in a rarity for me, I stay quiet. When I am ready for bed, Charlie says he’ll come a little later—he wants to do some work with Roscoe.

When I leave the bathroom after brushing my teeth, I see Charlie’s torso bent over the kitchen sink. I mean to give him a goodnight kiss, but he’s eating persimmons. His friend Arrow left a supermarket bag full on the doorstep. We’ve been watching a bowl of them ripen on the kitchen table. I like how they look, but I no longer consider eating them. We used to throw them at each other as kids.

One night Charlie described the tree in Arrow’s backyard. “It’s absolutely bare, except for these exquisite fruits hanging like ornaments, with their smooth-faced gloss and otherworldly pigment. Standing underneath that tree when it’s in full bloom, I feel like I’m living inside a Persian miniature.”

At the sink, Charlie looks like he lives inside a persimmon itself. He’s halved five or six and is sucking the muted orange slime from the overripe halves, with absolute abandon. Polyps of gooey fruit stick to his face and drip from his chin into the sink. This, somehow, is the man I love.

A common nightmare wakes me. I’m trying to get home but always take the wrong alleys and stairways; I get so tired of the circuitous trails and flights of stairs that I wake myself and am glad to be here.

Charlie hasn’t yet come to bed. Certainly he’s finished slamming persimmons. I put on my kimono and creep over to Roscoe’s room. Charlie is instructing the parrot to project his voice. “Let it boom, Roscoe, let it boom.” Charlie’s forceful voice demonstrates what he means.

I stand a distance from the closed door, but I hear them well. Charlie has come up with some bad rhymes that evidently go over well coming from the mouth of a parrot.

“Roscoe here. I’m going to be terse, it’s getting wertz.”

“The word is worse, Roscoe, worse.”

“Wertz, wertz,” the bird says.

Charlie, ever patient and encouraging, says, “Listen closely now with your mighty parrot ears: worse, worse.

After several more attempts, Roscoe nails it.

“Bravo. Kudos. Praise be to you, Roscoe. Now, let’s take the message from the top.”

“From the roof, Charlie?”

“Yes, from the roof, and try to take it all the way through the end of the message.”

I still don’t believe that it’s a parrot doing the talking, coming up with metaphors and all the rest, and yet the alternative is more frightening. What if Charlie is responsible for both voices, tossing the alternate voice, like a ventriloquist, from one side of the room to the other, in a faux training session behind closed doors? Talk about an alternative reality. How far is this practice from hallucination and madness?

“Okay, here goes nothing, Charlie,” the voice of the parrot says, “Roscoe here: I’m going to be terse, it’s getting worse. Forget defiance, believe the science.”

“Excellent job, Roscoe. First rate.”

“Top notch, Charlie?”

“Indeed. Now let’s try it over again.”

I become weary while leaning against the wall, and soon I slowly slide down it, curl into a ball, and sleep. When I awake, who knows how much later, man and bird are still at it, now with a new message: “Roscoe here: I need to share it, you’ve got to wear it.”

Awake now, I want the parrot to depart, like the noxious qualities of a dream, like the coronavirus itself, but the bird’s voice rings out again, as if to address me directly: “Roscoe here: I want to be crystal clear, the virus isn’t going to disappear.”

I made a birthday cake for Charlie today, a horribly misshapen pineapple upside down. It looked like it was going to explode at the sides and collapse. After buying two packs of mini birthday candles I decided to tempt fate and puncture the surface fifty-nine times. Charlie closed his eyes before blowing out the candles. I knew what his wish was and didn’t mind that I wasn’t included in it. Cutting the cake required surgical precision. Charlie asked for a small slice and I had the same. At that rate of consumption, the damn cake will last two weeks. It wasn’t bad, certainly better than it looked and, in the gloom that followed our attempt at festivity, I imagined stuffing the remainder of the cake in hearty hunks down the toilet.

Charlie had assumed the faraway look in his eyes that I’d first noticed after he turned Sally out of the house. It was as if a spell had been cast over him and I saw little chance of breaking him out of it, not that I really tried.

Earlier, before dinner, I asked Charlie to bring Roscoe to the table with us—that way, I thought, he’d have his group of three. Charlie obliged, leaving the parrot in his cage beside the table on a rolling tea tray. It seemed that Roscoe sensed the oddity of the situation. He spoke sparingly, but practically everything he said unnerved me.

I’d done a couple of fat, highly peppered filets on the stovetop with a flambé of cognac, along with au gratin potatoes and out of season asparagus from Mexico. Roscoe ate sparingly from a small bowl of seeds, nuts, and dried rosebuds that Charlie saved for him. After demolishing a bud, Roscoe addressed me directly. “A rose by any other name, Pina, would smell as sweet.”

I watched Charlie, as the parrot spoke. I still suspected ventriloquism but Charlie’s lips didn’t move a hair. “Have you been reading Shakespeare?” I asked the bird, after I regained my composure.

“I wish I could read,” Roscoe said, wistfully, or so I imagined. “Charlie reads to me and plays recordings.”

“You aren’t eating, Roscoe,” Charlie said. “Is something the matter?”

The parrot looked thoughtful and then he said, “I’m sated, Charlie.”

Roscoe’s speech was seriously freaking me out. It wasn’t just what he said, but how perfectly he’d mastered the tenses, and knew the appropriate thing to say at any given time.

“Did you teach him all this, Charlie?” I whispered.

Charlie shook his head. “I did at first, but now he’s on his own.”

“It’s not possible,” I said, full-voiced. “This isn’t real.”

“I’m afraid it is, Pina.”

Roscoe made a couple of peck-peck sounds and nibbled on a dried rose petal. Then with his head perfectly still, his eyes roved from me to Charlie. “I’m sorry to interrupt your party, Charlie. If I could I would take my leave.”

“Say goodnight to Pina, Roscoe.”

The parrot nodded his head. “Bonne nuit, Pina.”

Charlie lifted the cage and walked the bird to his spot in the second bedroom. I cleared the dishes and brought out small plates for the homely cake. When Charlie returned to the table I went out to the kitchen, lit all the candles on the cake, and brought it to Charlie, forced out a boisterous version of “Happy Birthday.” We sat and looked at the cake a moment, with its wide swath of burning candles. It reminded me of images I’d seen on TV of the new fires burning in Napa and Sonoma counties. That’s when Charlie closed his eyes, made a wish, and blew out the candles.

I could tell that he didn’t want to talk about Roscoe anymore, and the implications of having a genius parrot that could speak and reason as well as a bright human. Instead, Charlie told a story of a birthday party he had more than fifty years ago.

“I was seven-years-old that day. My mother prepared a box lunch, in an actual box with a folding lid, for six of my friends and me. Each kids’ name was written in huge block letters on the lid of the box.”

“How do you remember all that?” I asked.

“It was a memorable day. I was very proud of the boxes my mother made up. Each had an egg salad sandwich on white bread, a tiny box of raisins, a small bag of potato chips, a huge chocolate chip cookie, a napkin that said: HAPPY BIRTHDAY, and an assortment of party favors. I have a photo of that party which has helped me keep the memory fresh.”

“How often do you look at the photo, Charlie?”

“Every ten years or so, but here’s the thing: of my six friends, five were boys. The girl, Rosalie, lived across the street and went to the Catholic school, St. Bart’s, while the five boys went with me to Maxwell Cubbins Elementary. Rosalie was actually my best friend, but I didn’t want the boys to know that. She had five older brothers and was one hell of a tomboy, much more daring than me. Rosalie taught me a lot of things that a boy should know how to do, things she learned from her brothers, like how to whistle and tie a slipknot. She’s the one who showed me how to make a reliable slingshot. She carried a pocketknife with a buffalo on it and we took turns carving our initials on trees and fences.”

“Did you carve your initials inside a heart?” I asked.

“No, no, it wasn’t like that.”

“Don’t worry, Charlie, I’m not jealous.” That got us both chuckling. I had no idea where this shaggy dog story of Charlie’s was heading, but it was clearly taking us far from Roscoe.

“The boys at the party wouldn’t talk to Rosalie so I didn’t talk to her either.”

“Typical.”

“And when we started to eat our lunches, all the boys began with our cookies, and made fun of Rosalie for eating her sandwich first. That’s when she choked on a big gob of sandwich. We were gathered around the breakfast room table, and my mother hung back in the kitchen, watching us from a distance. Rosalie sat directly across the table from me and I could see that she was choking. I called for my mother. This was before the Heimlich maneuver was part of the culture. My mother ran over and slapped Rosalie hard on the back a couple of times and she finally coughed up the big chunk of sandwich.”

Charlie gazed at me a little sheepishly before continuing. “Artie Bosco, who sat next to Rosalie, and had pulled his chair as far from hers as possible, as if she had the cooties, said, “Geeze, Rosalie, you got to chew your food.” She stuck out her tongue at Artie and just then he noticed the floor beneath her, and screamed: “Look, look what Rosalie did.” The other boys and I dashed over to witness the puddle she left on the floor. Poor Rosalie lashed out with both her arms and scooted out of the breakfast room and on out the front door.

“Later,” Charlie said, “when I was in bed, I remembered the look in Rosalie’s eyes and, for the first time thought, it must be harder to be a girl.”

I had the feeling that Charlie made up his birthday story from whole cloth. I was impressed with all the details, and yet if there’s anything I’ve learned about Charlie, it’s that he’s a detail man. But what seven-year-old boy has that kind of insight—that life must be harder for a girl? Did Rosalie actually leave a puddle of pee on the floor? Did a girl named Rosalie even live on Charlie’s block? Was the whole idea of the box lunches a fabrication? I didn’t press him on the veracity of his story. Once he told it, more than likely as a diversion from Roscoe, it became part of his past, just as an improbable dream does.

Of the new fires, the Glass Fire is closest to us. It has blazed over the Mayacmas from Napa Valley, where it destroyed numerous wineries and houses, all the way to the east end of Santa Rosa, and across Highway 29 into the retirement community of Oakmont, which evacuated all 4500 of its residents. Charlie and I watched on the news as the oldsters from the Oakmont assisted living facility lined up with their walkers outside at 11PM. Many were in their bathrobes, waiting for the next bus. One old woman in a wheelchair held a teddy bear in her lap. Charlie teared up as we watched because his mother had moved down to Oakmont, to be close to him after his father died, and she spent her last days in Oakmont’s assisted living facility.

“She loved it there,” Charlie said, “particularly in the dining room. She sat with her friends at a big table and the Latino waiters flirted with the old ladies as they recited the choice of entrees and asked if they’d like another scoop of ice cream. My mother said it felt like they were on a cruise. That was before cruise was a dirty word.”

The fires are still a long way from the town of Sonoma but the smoke is bad and getting worse. Charlie and I talk about where we could go and never come up with a solution, even for the short term. It’s gotten smoky out at the coast. Deciding where to live is becoming an existential quandary for many Californians, and it’s extending beyond the state and across the entire west coast. Charlie says, that with climate change, Northern California will eventually become a desert; fires will have less fuel and no longer be so widespread. I don’t think we have the time to wait for that, and I’ve never fancied living in the desert.

Tonight, before we sat down to watch the first presidential debate, I told Charlie about an article I’d read about five African grey parrots in a wildlife park north of London. They egged each other on with vast vocabularies of swear words. Park goers loved it and swore back at the parrots, but the directors of the sanctuary removed the birds from public view because they were concerned for children who might get caught up in the crossfire of obscenities. Charlie got a good laugh out of that. Telling him about the “potty-mouthed parrots,” as the article worded it, was my way of letting him know I now understand how remarkable these birds can be and that I will be more accepting of Roscoe.

Charlie was in a good mood because he’d had a congenial conversation with Sally earlier in the day. She’d called to apologize for her behavior the other night. She told him that she was safe and very much looking forward to moving into her new apartment, the day after tomorrow.

“I have hopes for her,” Charlie said. “I’m glad she’ll be nearby, but not here.”

Neither of us was prepared for the craziness of the so-called debate. Charlie and I have been alternately repelled by the news. First I needed to have a moratorium, then he, now me again. I had to walk away from the TV thirty minutes after the debate started, but Charlie seemed to get a kick out of the debacle. He kept shouting from the couch: “Trump’s killing any chance he had.” “Biden just said, ‘Will you shut up, man?’” “Trump won’t condemn white supremacy.” “Biden called Trump a clown!” I finally went back to the couch and sat beside Charlie for the duration since there was no getting away from it. Instead of watching the television, I watched Charlie. “Trump’s cooked his own goose with this performance. How do you think his ‘suburban housewives’ are enjoying this?”

I heard my nonna’s voice coming from outside my childhood home, and rushed from my bed to the window. She stood beside a disorderly silver maple, dressed in her black widow garb, except for an uncharacteristic straw hat, ringed in faux cherries. I threw on one of Charlie’s flannel shirts but didn’t bother buttoning it. Down two flights of stairs to the street took an eternity. I could still hear her voice—it was all its verticality, climbing up and down the laddered rungs of her throat.

She sang out in spiky Italian: Il mondo sta volgendo al termine, the world is coming to an end. I put on a mask at the front door. Charlie is always making new ones, this one from a print with cherries and their stems. Sometimes the world aligns in harmonic convergence. This must be one of those times.

When I reached the street, my nonna was nowhere to be seen, but Charlie’s daughter Sally stood under the silver maple with a colander filled with wet, glistening cherries. A blood-red scar of cherry juice spread like a birthmark across her face. She kept shoving cherries into her mouth and spitting out the seeds.

“Have you seen an old woman?” I asked.

“I haven’t see anybody. I keep to myself.” Sally wiped her mouth with the back of her hand and now it, too, looked like a great wound.

“It was my nonna,” I said, “my grandmother.”

Sally spit out some seeds. “How old is she?”

I stopped to do the math. “One hundred and fifteen.”

“She must be on a salt-free diet and mainlining Vitamin D. I know for a fact that she’s ingesting plenty of fiber.”

Apparently, Sally had eaten enough cherries because she now picked them out of the colander and began throwing them at passing cars.

I was overcome with sadness at the prospect of not seeing my nonna again, and decided to go back in the house, but when I turned from the street, the house was gone.

Sally’s scream woke me. Charlie had already left for his early morning walk. When I got out to the living room, Sally was pacing back and forth, barefoot in flannel pajamas, mumbling to herself. I caught her eye and asked what the matter was. She looked back at me as if I should know. “That bird,” she said finally.

“He scared you?”

“Well, yes. I woke, sat up in the futon, and that bird said, ‘Top of the morning to you,’ in a fucking Irish brogue, and when he saw me freaking out, he said, ‘Is everything copasetic, dear?’ in a voice that sounded like my Aunt Emily’s. That’s when I screamed. Sorry about that.”

“No worries. Yeah, your dad’s really got Roscoe trained to say all kinds of shit. It is pretty spooky.”

“How can a bird do that?”

“Ah, now you’re asking questions too deep for me to answer. You know the person to ask.”

I brewed a pot of coffee and Sally and I sat apart from each other out on the deck. The fog had come in and it was nippy outside. I want to help Sally feel comfortable, not just about Roscoe, but about staying in her father’s house, with me around. That will be a trick because it’s not something that I’m comfortable with.

I gazed into Sally’s pretty moon face and the fetching gap between her front teeth. Her coloring is much darker than Charlie’s, and yet I can see a likeness around her eyes. As I sipped my coffee, I tried to imagine what it will be like for her to start over in the middle of a plague, and found myself thinking about the mess I was after Marco, my late husband died.

Sally smiled at me. “Where’d you go?”

Her question surprised me. It wasn’t as if we were in the middle of a conversation.

“You don’t have to tell me, but I noticed your mind take off on a jet and fly from one hemisphere to another.”

I shook my head. “You could see that? Are you clairvoyant, Sally?”

“Hmm,” she said, cryptically, before changing the subject. “Hey, I can tell that you’re good for my dad,”

“How so?”

“Well, for one thing, I haven’t noticed him smile so much in years.”

“I think he was just glad to see you, Sally.”

“Nah. He seems younger and like he’s got some kind of purpose.”

“His purpose is Roscoe.”

“Why don’t you want to believe what I’m telling you. Pina?” she asked, as if she were the elder.

“I don’t know . . . it makes me bashful.”

Sally laughed at that.

“What? Am I too old to be bashful?”

“Shush. I see the way the two of you look at each other. ‘Nuff said.”

“Maybe we were just putting on a show for you.”

Sally shook her head, as if I were hopeless. She finished her coffee and stood. “It’s time for my yoga practice. I want to see what that bird has to say when I stand on my head for fifteen minutes.”

“I can bring him out to the living room.”

“No, no, I need to make peace with Roscoe.”

I stayed out on the deck until Charlie returned from his walk, musing about the idea that somebody might love me, and my resistance to it.

This morning Sonoma is the second coming of Pompeii—flakes of ash falling from a yellow orange sky. We saw images of San Francisco in complete darkness at ten in the morning. In Sonoma the air quality reading was surprisingly decent. Apparently the smoke had risen very high in the atmosphere. A layer of marine air (I think that means fog) served as a buffer.

Charlie and I walked to the square. People carried on as if all this was normal. Deliveries were made to restaurants operating at quarter capacity. Tourists window-shopped in their masks. When weirdness becomes the norm you either roll with the punches or go mad.

It’s been two weeks now since Sally’s moved in. Charlie and I have danced around the inconvenience and we both know something has to give. The condo is too small for three people and a parrot in the middle of a plague.

Charlie took my hand and led me over to the duck pond—the site of our first meeting. We sat on the same bench, but no longer six feet apart. A single mallard glided around the pond and Charlie commented on him: “Everybody is a little lonely these days.”

I agreed. Since Sally moved in, I’ve felt unbalanced in a way that reminds me of loneliness. Lonely in a crowd. I asked Charlie how his work with Roscoe was going.

“I wouldn’t call it work,” he said.

“What would you call it? You’re in there with him for eight hours a day.” I didn’t like how that came out; it sounded so bitchy.

Charlie offered a thin-lipped smile. “Roscoe has an insatiable appetite for language.”

“So you’re feeding him words eight hours a day.” That too sounded bitchy. I couldn’t help myself.

Thankfully, Charlie changed the subject. “I’ve rented an apartment for Sally in Sonoma. It’s a really nice place, down on Broadway. I haven’t told her yet. I wanted you to know first. The problem is she can’t get in until October first.”

“That’s three more weeks. Maybe I’ll move back into Vince’s condo until she moves out.”

“Or I could take a driving trip with Sally,” Charlie said. He had a skeptical look on his face as the idea of the driving trip unfurled. “Okay, let’s see, because of the fires you can’t drive north, can’t drive south, and west you have the Pacific Ocean.“

“Sounds like you’re heading east young man, with your girl and your parrot.” Somehow saying this set us both off laughing. I hadn’t laughed so hard for a long time, not in modern memory, and the unspoken tension between Charlie and me lifted at least as high as the marine layer.

Sally was thrilled to hear the news about the apartment Charlie rented for her and said that she’d be happy to cook dinner. I didn’t look forward to the prospect and ended up chiding myself for assuming that whatever she cooked would resemble hippie chow.

I wasn’t far off. Sally made an African peanut stew that was moderately palatable. Along with a preponderance of peanut butter, she added sweet potatoes, brown rice, and collard greens from her garden. Before leaving the Lost Coast, she filled the back seat of her car with her harvest, and we are still in possession of more collards and kale than any three people could eat in six months. This dish was definitely stick to your ribs type fare, but I’m not sure whether my ribs will ever be the same.

“Any ideas for a wine pairing?” Charlie asked.

I suggested the heartiest red in Charlie’s cellar but Charlie doesn’t have a cellar and the only decent red we had on hand was an Oregon Pinot, which didn’t have nearly the tannin or starch to stand up to the stew.

Charlie, compensating for my polite response, was full of compliments for Sally’s dinner.

“Sally never used to cook,” he said.

“I cook all the time now.”

“Remember how you’d say, a contemporary woman should not spend any time cooking, because that reinforces the stereotype that a woman’s place is in the kitchen.”

“Yeah,” Sally said, shrugging, ”I said a lot of stupid shit, but at least there was some logic in the thought.”

“So you’ve evolved,” Charlie said.

“Or devolved.” Sally aimed a fat forkful of peanut stew into her mouth.

Charlie smiled at me and at his daughter. He clearly looked like a happy man. And, yes, I am beginning to believe he loves me.

Sally blotted her lips with her napkin. “I think we should do raw tomorrow night. I’m thinking a raw vegan lasagna.”

Neither Charlie nor I responded and I sat there trying to come up with the perfect wine pairing.

“Or should we do broccoli balls and cauliflower rice sushi?”

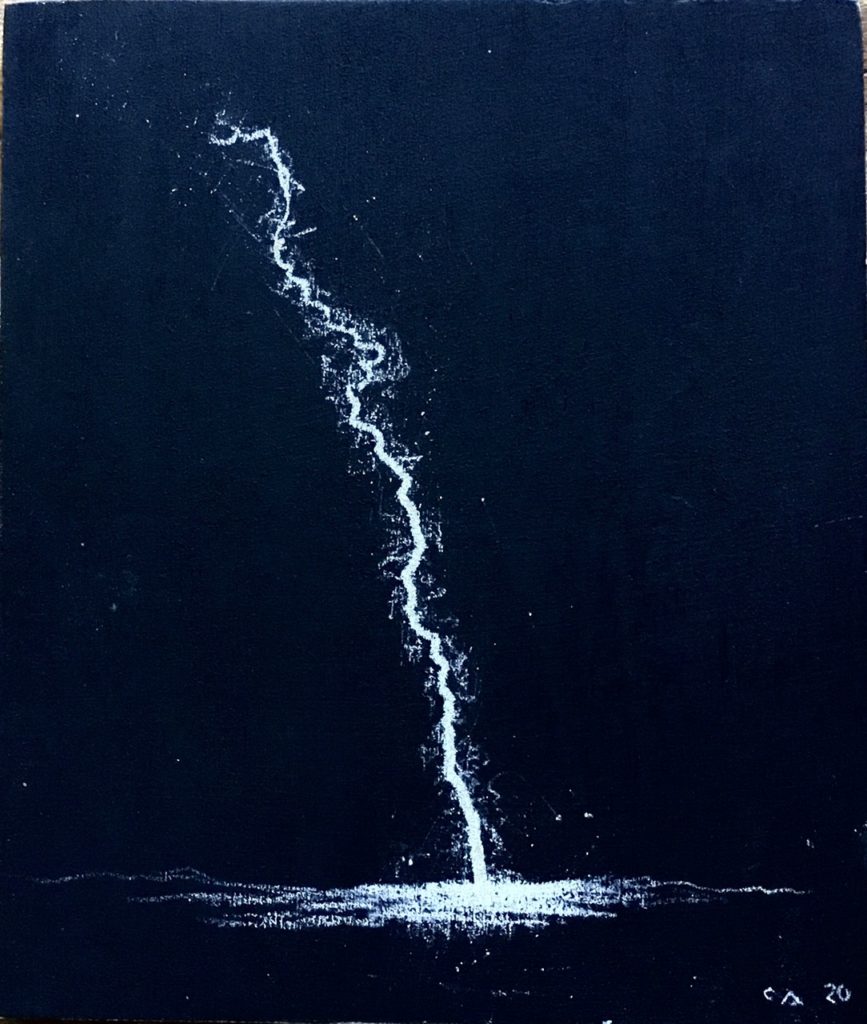

On Monday, Charlie and I took the morning off and headed to the ocean. The heat in Sonoma has been brutal, with the addition of something we rarely have: high humidity. We saw the pulses of dry lightening and heard thunder, the night before. The little bit it rained didn’t correspond with the lightening strikes, so numerous fires broke out.

We studied the skies as we approached Muir Beach on Monday. To our north, a stark black swath of sky was divided, by a line as hard as the horizon, from the mottled overcast sky above us. We guessed we were in the clear and lugged our blanket and cooler, filled with enough picnic fare for a big clan, onto the beach. We saw distant lightening, but according to the forecast the skies were due to clear in the next hour. Almost as soon as we reached the beach, the edge of the black cloud spat rain and the wind went dervish with the sand, blasting our bare legs. Families packed up furiously and we all dashed back to the parking lot like the end of the world was upon us. Defeated, Charlie and I retreated to a tiny beach he knew in ritzy Belvedere, Paradise Cove—right across the bay from San Quentin, where half the prisoners have tested positive for Covid, a fact I couldn’t get out of my head as we had our picnic on the beach. I must have appeared abstracted as I ate my egg salad sandwich, because Charlie asked me what was going on. When I explained that my head was filled with prisoners, Charlie said, “Maybe they’ll let the healthy ones out to fight fires for a dollar an hour.”

The edge of the black cloud spat rain and the wind

went dervish with the sand, blasting our bare legs.

Later, we swam; the water wasn’t too cold but it felt clammy, as the bay usually does. The day’s saving grace was the three-dozen Hog Island oysters that we picked up at Larkspur Landing, on the drive home. They were the sweetest I’ve had in a long time. What a bounty, heaped on an ancient Corona platter, with a fine mignonette that Charlie made, with sliced shallots soaked in champagne vinegar.

This morning the smoke in the air is bad, with a dusting of ash on the deck. We’re getting alerts of evacuations, a long distance from here, but it’s just beginning. Rolling blackouts are threatened, but we haven’t seen any yet. There are fires burning in Vacaville. Interstate 80 is closed between Vacaville and Fairfield. A huge ring of fire surrounds Lake Berryessa. The entire city of Healdsburg is ready to evacuate. From there, it burns north of the Russian River into West County, and nearly to the ocean.

We closed everything up last night to keep the bad air out. Charlie’s even thinking about turning on the old air conditioner. I told him I don’t mind the heat, but I think he’s worried about his parrot.

“Put a damp towel over his cage,” I suggested, “That’s how McTeague protected his canary when he was on the lam in Death Valley.”

“How did that turn out?” Charlie asked, knowing full well that both McTeague and the canary perished.

“Hey, this isn’t exactly Death Valley,” which was in the news last week for hitting a temperature of 130.

A little before noon I saw Charlie walk into the parrot room with a wet towel.

I had my first client via Zoom today: Aubrey Kincaid, a prodigious stutterer in his mid thirties. Aubrey wore a well-pressed Oxford cloth shirt for the occasion. I kept things simple in a sleeveless linen dress, with a red onyx pendant that Charlie gave me the night I moved in.

For some reason, I waved at my client. “How are you, Aubrey?”

“Good. Good,” he said, nodding.

“It’s nice seeing you. What a lovely shirt.”

Aubrey took an audible sniff of the air. “I just iron-ironed it. Sooooo,” he said, stretching the word out, a trick I taught him for gathering his composure, “I have-have been doing my exercises.”

“I can tell.” It was true. Aubrey spoke with more fluency than I remember. In the past he stammered over nearly every word and his head-jerks, which often accompanied his speech delays, had disappeared.

Aubrey worked as an accountant at a firm in Corte Madera and had gone through a dark period, losing clients he attributed to his stuttering. That’s why he’d started therapy in the first place, about six months before the pandemic hit. From what Aubrey told me, he’d been as traumatized by his childhood speech therapy as by the stuttering itself, so I took a very relaxed conversational approach to our sessions, mixing in a light exercise or two. I’d gotten Aubrey in the habit of reading aloud to himself everyday, and also exaggerating the head jerks that had become part of his stuttering routine; full awareness is the best path to elimination.

My goal for the first session was to have an easy conversation with Aubrey. That would allow me to do a proper evaluation after all the time’s that’s elapsed.

It delighted me that Aubrey kicked off the conversation. “Soooo, what’s new with you, Pa-pina?”

Aubrey had never managed to pronounce my name without some sort of a hitch and this time a guttural grunt followed his flub.

I carried on without pause. “I moved to Sonoma,” I said.

“I love Sa-sa-mona,” he said, leaving the damaged name alone, as I’d counseled, and continued: “I really like the town square. Have you been to The Girl and the Fig?” Aubrey beamed after saying so much without a problem.

“Yes, yes. It’s one of my favorite spots in town.”

“Me too. Soooo, Pa-pina, you look fine.”

Nice as it was to hear that I looked fine, Aubrey’s comment was inappropriate. I wondered if messing up my name had led him somewhere he hadn’t meant to go. In any case, after his head jerked hard right for the first time during our conversation, he carried on as if nothing odd had happened, which is pretty much the fate of a life-long stutterer—carrying on as well as one can.

Soooo, Pa-pina, you look fine.”

Nice as it was to hear that I looked fine,

Aubrey’s comment was inappropriate.

“I went out on a date,” he said.

“Oh, good.”

“It was kind of a disaster.”

“I’m sorry.”

“It wasn’t so much the sta-stutter-stuttering. I could deal with that. We met for coffee at an outside café. The young lady didn’t look like her photo. She was fa-fat. I, you know, I didn’t want to be rude, but I couldn’t think of any-any-anything to say.”

“But you hung in there.”

“Yep. I hung in there.” I could tell that Aubrey was studying his own reflection, mugging a bit for the camera.

“Good for you, Aubrey.”

“I also went to a Ba-ba-black Lives Matter protest in the city. Guess what,” he said and then chuckled. “My-my sign didn’t stutter.”

“What did it say?”

“No-no justice, no peace. I’m-I’m try-trying to get in touch with my-my privilege.”

“That’s great, Aubrey. Me too.”

He nodded his head proudly. “Except-cept, I don’t-don’t feel that privileged.” Aubrey then turned quiet. I could see the old shame spilling over him.

I carried on much of rest of the conversation, asking Aubrey about his job and his twin sisters who he’s worked hard to forgive after they teased him relentlessly throughout his stuttering childhood.

Aubrey chimed in with short answers and we agreed to Zoom the following Thursday.

I can’t get enough of Charlie lately. When I say that to myself, I think first of Charlie’s body and then of his soul. They both satisfy me. Which says a fuck of a lot. The funny thing is I’d rather not see Charlie much during the day. I’m at my desk trying to figure out how many clients I can work with under the circumstances. During the long pandemic months while I resisted the opportunity to work from a distance, I reinvented myself. I truly believe that. The hours of solitude, which frightened me at first, have now become a necessary feature of my daily life. I knew that moving in with Charlie would compromise my solitude to a degree, but I decided the trade-off was worth it.

During the recent hot days Charlie has come in to gawk at me, plotzed half naked in the executive swivel chair I commandeered from him. I don’t mind seeing him for a flash or having a quick lunch with him, but I prefer to save him until later, for love and play. We are still so new with each other that it’s premature to claim that familiarity breeds contempt, but perhaps I fear that if we are not rigorous about maintaining some distance contempt will develop.

I’m still puzzled that I could fall for a man who spends the bulk of his day training a parrot. I have no idea what he’s after, but he carries on like a mad scientist. He tries to keep the extent of his Roscoe training from me, claiming he’s in a rut, working on dead-end animation projects. I know better. Anyway, Charlie isn’t a dead-end kind of a guy. He has what’s described as the happiness gene; the dude is bubbling over with serotonin. It cheers me to be with a man, who’s neither cynical nor sarcastic, features of my nature that I’ve, at least temporarily, put on hold, but which thrived in the years I spent with my faux husband Vince. Does my choice of Charlie mean that I’ve evolved or does it portend an inevitable clash of natures that will destroy us? I’m inclined to believe the latter, but there’s no sense in counting my dead chickens before they croak.

I’m still puzzled that I could fall for a man

who spends the bulk of his day training a parrot.

The last two nights Charlie persuaded me to watch the Democratic convention. He gets tears in his eyes during all the human-interest stories, and when Obama made his marvelous speech the night before, Charlie clutched my hand. Last night the brave speech by the stuttering boy who met Joe Biden brought me to tears. I hesitate to believe this, but I think Charlie’s humanity is rubbing off on me.

One of the convention commentators mentioned that to help himself as a childhood stutterer, Biden read poems by W. B. Yeats.

“That’s the coolest thing I’ve ever heard about Biden—the dude stuttered his way through Yeats poems.”

“Have you ever used Yeats with your stutterers?” Charlie asked

“Not yet.” Then Charlie surprised me by reciting the first stanza of “The Second Coming”:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Hearing Charlie recite the lines moved me. “How did you memorize that?” I asked, foolishly.

“Oh, I’ve memorized a lot of poems. This one seems appallingly on point for the moment. It was written in 1919 at the end of World War I.”

“And, God damn,” I said, “I don’t know how a stutterer could get through that poem. Every other word is a trigger. Turning, widening anarchy, conviction, passionate.”

And then Charlie, who does not stutter, recited the entire poem not, as Vince does, with a lofty self-consciousness, but as a common man who wants to travel with the words and their meaning down the crooked road of his life.

She shouldn’t have told Charlie in the first place. Why did she? You sleep with somebody and suddenly you’re soul mates, ready to reveal the darkest secrets of your life? Now Charlie won’t let her drive to the city alone. She tries to convince him that she’ll be fine, that it is really no big deal, but he insists it isn’t safe for her to walk around the Tenderloin alone.

“I’m not going to walk around. I’ll drive to the block Vince said, open the window when I spot him, and hand him the money.”

“It might not happen like that,” Charlie says. “And what are you worried about, that Vince will see us together and jump to conclusions? As far as he’s concerned, I’m just your escort.”

“Some escort,” she says, and kisses him on the forehead. No need to spoil the sweetness between them so soon.

“Give me fifteen minutes,” Charlie says, enthused for the adventure. “I’ve got to go back to my place, take a quick shower, and put out some feed for Roscoe.”

Pina thinks of driving off before Charlie returns. This should be between Vince and her. How many ways can she betray him? Her guilt is really barking at her. She didn’t have to tell Charlie about this, but it wasn’t an accident.

Before she’s got herself fully dressed, Charlie’s at the door with a cooler and a sack full of homemade facemasks. “I made us sandwiches,” he says, “and one for Vince.”

Great, she thinks, we’ll have a little picnic in the Tenderloin.

Pina insists on driving and stops at a cash machine on the square. For a while they manage to talk about everything except their mission. Charlie has a lot to say about one of Trump’s pet projects: Space Force. The new Space Force flag was unveiled yesterday in the Oval Office. “They just went and stole the logo from Star Trek,” he says, “and then Trump calls this rocket they’re pretending to develop, a ‘super-duper missile,’ which somebody pointed out later on Twitter, was the name of a porn star in the eighties.”

“Anything to distract us from his murderous negligence and misinformation.” Pina doesn’t want to wade any further into her anger toward Trump, but maybe she should change her strategy. Vince’s description of the heroin consolidation plan comes to mind. It allows you to roll your problems into one—staying high. She might do well to combine her grievances into single-minded hatred toward Trump, except that such sustained animus would likely make her ill.

Charlie does a hemiola bongo riff—two beats against three—with his hands on the dashboard, and she wonders if, despite his good cheer, he’s a little nervous about their adventure.

He raises his index finger, altering the beats. “Heard this town hall with Joe Biden and Stacy Abrams the other night. He says he’s not going to pardon Trump.”

“Normally I’m against capital punishment, but I’d enjoy seeing that man lynched.”

Charlie’s head jerks back and his hands come off the dash. Apparently, she’s shocked him. “Would you participate in the lynching, Pina, or just be a spectator?”

She doesn’t want to go there, doesn’t want to let Charlie know what horrid thoughts she’s capable of. “I can’t think about Trump anymore. He gets into your head and you’re infected with another virus.”

They drive in silence for a while and she tries to focus on the task at hand. Will it go as she hopes, simply find Vince and hand over the dough? Or do they try some kind of intervention? How would that look? Is such an intercession even possible with a man who’s likely infected, in a time when back-up services are unavailable?

“So how long do you think the freeways will be empty like this?” Charlie asks.

She doesn’t want to make small talk. This is one reason she wanted to drive alone—single-mindedness is required.

Charlie drops a hand on her thigh and squeezes it. “Are you okay, Pina?”

No, she’s not okay at all, but she wants to talk even less about herself than this and that. “Yeah, I’m fine, but in response to your earlier question, I think it’s going to be a very long time, if ever, before the traffic becomes as it was. How many people are going to return to office buildings in San Francisco? All these giant tech companies are telling their workers that they never have to come back to the office, and without those workers present all the restaurants and services that depend on them will fold.”

“Do you think people will leave the city en masse?”

Pina thinks of the character in the Hemingway story that says, “Will you please please please please stop talking?”

Charlie answers his own question: “I mean, it’s like somebody said, ‘Why pay San Francisco rents when it’s not San Francisco out there anymore?’ The office buildings may be half empty.” His hands throb in the air for emphasis. “And tens of thousands of people won’t be able to make the rent.”

“Homelessness will be rampant,” she chips in. “The city will take on the flavor or, should I say, redolence, of Mumbai during a heat wave.” So she and Charlie are having a delightful moment of dystopian sharing. She wouldn’t have thought him capable of such darkness.

“Yep.” Charlie goes back to his two against three beat rhythms on the dashboard. “Anybody with money who stays will have to hire guards to protect them from the huddled masses.”

“Soylent Green is people,” she says, just to add another accent to the dark stew they’re prepping.

Charlie backs off the bongos and glances at her with a wary look. There’s something about his expression that reminds her of a teenage boy, somebody she vaguely remembers from high school—Jason, a boy she briefly went out with. The moment she broke-up with him his face puckered in sadness. Charlie’s expression is similar but he’s wearing his grief for a different reason.

“Do you really believe all that’s going to happen, Pina?”

She does, and she would gladly go on with the bleak recital, but thinks it better to offer Charlie some comfort. “I do think some of that will happen, but on the flip side, there may be opportunities to rebuild the city in a more equitable way. Young people will move in and reinvigorate the place with much greater diversity. Finally, they’ll be able to afford to live in the city.”

By the time they reach the bridge, they’re both quiet. Not even the gloom can erase the majesty of the Golden Gate. Years ago in school she worked with a girl, maybe seven or eight, who had a bad stutter. This girl always liked to talk about heaven. Maybe she came from a religious family. One day Pina asked her what heaven was like. Aside from the stutter, her response was quick: “Hev . . . hev . . . heaven is li . . . is like the Golden Gate Bridge.” She pronounced the balance of the sentence in one fell swoop. Pina repeated it: “Heaven is like the Golden Gate Bridge,” and the girl said the sentence perfectly. It may have been the first time in her life that she spoke without a stammer.

Pina speeds through the Presidio tunnel toward the Marina. How she would like to dally here, take a walk with Charlie along the beach at Crissy Field or past the sailboats and fishing crafts moored in the Marina. How nice it would be to drive to North Beach, where today she’d probably find a parking place. A creeping gauze of nostalgia drapes over her. She’d like to eat at one of the old family-style restaurants she used to visit with her parents, more than forty years ago: The New Pisa, The Green Valley, The Golden Spike. All of them, like her parents, long gone.

She turns away from the Marina, and heads south on Divisidero. Two blocks up, she pulls over. “Charlie, I need you to sit in the back seat. From now on you and me are not Covid bonded.”

“Got it,” he says, “I’m nothing more than your escort.” He shifts quickly to the back seat and she smiles at him in the rearview mirror.

The city sparkles, after the morning rain—a rare mid-May rain that gives the air a crisp brightness. Even the old white apartment buildings look like they have been blessed.

She turns left on Bush and her nerves flare; a knot forms in her stomach. What will Vince look like? Will she even recognize him? What will he say when he sees Charlie?

Right on Hyde, she braces herself. A few blocks south, and the scattered homeless take over the landscape. All the work the city’s been doing to try and house them is either a fiction or ineffective. Her mind struggles to synthesize what she sees, a universe of smashed leavings: broken crutches, filthy tarps, a shopping cart missing a wheel, a picket sign leaning against a wall that says, Living wages, another shopping cart filled with smashed cans, stacks of cardboard, newspapers a flutter, a row of upturned milk crates, broken bottles, a length of hose coiled around a lamp pole.

Finally, she lets herself see the people: a woman with sores around her mouth, marching back and forth in front of an empty storefront, a man sitting on a crate, smoking, another eating a chicken leg that looks to have no meat left on it, someone coiled under a disgusting blanket, sleeping directly on the sidewalk, two young guys spending their extended adolescence on the street, playing with a rabid-looking dog, a cowboy bandana draped around its neck, a stout Latina in a nurse’s uniform, the only person she’s seen yet wearing a mask.

She wants to turn left on Ellis, but it’s a one-way she can’t enter, so she goes down to Eddy, glancing back at her escort in the mirror. His expression is as grim as she’s seen it. “He could be anywhere around her, Charlie. I’m circling back to Ellis, this is Leavenworth.”

“Roger. I’ll look right, you look left.”

She passes The Black Cat, a swanky bar with a jazz room downstairs that she and Vince frequented a couple of times. There’s a crooked line outside of a bánh mi shop, as she turns west onto Ellis, but Vince isn’t waiting for a sandwich. Social distancing doesn’t seem to be a thing here; small clusters of people talk together. She drives so slowly that she’s drawn the attention of some of the folks on the sidewalk.

“Haven’t seen him yet,” Charlie reports.

A car behind her, that seems like it’s come from out of nowhere, starts honking. Now more eyes from the sidewalk are turned to her.

“You better pull over.”

“Why’s everybody staring at us?”

“They think we’re cops.”

“Really, do we look like cops?”

“Turn the corner and pull over.”

She doesn’t know how she feels about Charlie giving orders. There’s another car honking behind her, but before she gets to the corner a very skinny man in a Giants’ cap tosses something at the car that actually shakes it.

“What the fuck was that?”

“I don’t know, a hunk of concrete? Come on, turn the corner, Pina.”

She turns back down Hyde and double parks in front of a Chinese laundry called Alice’s, with a window filled with thriving succulents. The knot in her stomach is now throbbing. She gets out of the car and Charlie follows her. The big boulder, or whatever it was the guy tossed, carved a good-sized crater into the passenger door. Charlie comes close to have a look. “Social distance,” she barks, and then softens, “Sorry.”

Charlie backs away from her. “You stay here and I’ll find him.”

“No, I’ll go.”

Charlie doesn’t look amused. “I’m not going to let you go alone, Pina. Let’s park the car now.” He climbs into the back seat.

Pina pulls out without looking and almost gets clipped by a grocery truck that just turned onto Hyde. She finds a questionable spot, half in the red, on Eddy. “Oh, my nerves are shot.”

“You stay here, Pina.”

She takes a long breath. “We both go.”

Charlie walks ahead and she pretends to stay six feet behind him. They head up Jones past Jonell’s Cocktail Lounge, a true dive bar that Vince took her to once. That was the kind of adventure he enjoyed in their early days together. Once he discovered that she would drink anywhere, he brought her to many of his old watering spots.

As they turn onto Ellis, a man with a Jamaican accent, leaning against a wall between storefronts, speaks to Charlie: “Wha gwan, professa. A lil hep fi a man tween opportunities.”

She inches closer to Charlie, surprised to see him reach into his pocket and hand the guy a five dollar bill.”

“Tanks for da cheddar, professa. Remine me zacly wha yu be a professa o.”

“Magic,” Charlie says, without hesitation.

“Professa o magic. Ha ha ha. Dat’s shot. Yu gots a lit mo magic fi me?”

Charlie shakes his head.

“Yu cool, professa.”

“I have something else for you.” Charlie reaches into his shoulder bag and hands over a large plastic bag with a mask in it. “It’s clean.”

“Dat’s shot, professa. The Jamaican pulls out the mask, which is zebra-striped and tries it on.

As Charlie moves along, the man addresses her, “Sistern, yu wid di professa?”

She shakes her head.

“Thot yu was. Priddy sistern, yu god a liddle cash for my rash?”

“Not today,” she says and hurries along.

“K. Yu catch Professa Magic, cum back marow.”

There are more people than she expected on the street, some under blankets and others, a bit like ghosts, camouflaged amid the gray storefronts and cardboard castles. There are also folks, who live or work in the neighborhood, numerous Vietnamese, even mothers with children, going about their business as if this tragic tableau was normal, as it is for those who live here.

Pina falls a ways behind Charlie, allowing more than ample distance between them. She’s a little bit surprised that he doesn’t turn back to make sure she’s behind him. Clearly, he has more faith than Orpheus did. She walks quickly past the skinny guy in the Giants cap that tossed the boulder at the car, but before she gets far she hears a laughing female voice shout: “That’s the woman, that’s the woman just sitting there in her car.”

She looks right and left for Vince and three quarters of the way up the block, past two men playing checkers on a cardboard box turned on end, she gets her first glimpse of him. He’s standing up, his wide shoulders tilted to the side, speaking with Charlie. She feels both a rush of joy that he’s alive and horror that he’s standing out here ravaged. How could a man degenerate so quickly?

As she creeps closer she sees that the left side of Vince’s face has a raw bruise, and his lower lip is cut. He’s wearing a torn flannel shirt over blue scrubs, and a pair of brogues with no socks. She stands back by the curb. That’s as close as she’s going to get. “Vince,” she says, “I’m so glad we found you.”

“This is where I told you.” He glances from one of them to the other. “So when did you two become an item?”

Charlie begins to explain, “No I just came down . . .”

“Like I give a damn. You got the money?”

“Yeah, we have the money.”

“Cat’s got Pina’s tongue. Go buy her a drink, Charlie. She needs a drink. Now give me the money.”

“You’re not looking so good, Vince.”

“Well the beauty contest was last week.”

It’s true, she’s lost her tongue and she feels that if she opens her mouth she’ll stutter like one of her clients. She’d like to run and just keep running. Somehow she’s lost all her agency. She thought she could rise to the occasion. It’s all she can do to stand here and not to pee herself.

Charlie is holding his ground. “I’m going to get you to the hospital, Vince.”

“Who do you think you are, Charlie, the adult in the room?”

It ‘s a funny comment because that’s exactly who Charlie is acting like. She’d laugh if she weren’t drenched in shame, for what? Having lost her voice? Betraying Vince, not so much with Charlie, but as a mate, somewhere along the line. Surely she has some responsibility for the fact that he’s come to this.

“Give me the money,” Vince hollers.

Charlie reaches into his shoulder bag and pulls out a pair of purple gloves that he slips on. “Okay, I have a mask for you and I want you to put it on.”

“What the fuck?” Vince takes the bagged mask and tosses it on the ground.

“Pick it up and put it on, Vince.”

Vince slumps and sways back and forth a moment. His eyes are rheumy and he looks like he might collapse.

Charlie picks up the mask and ties it around Vince, who mumbles something unintelligible. “Lean against the wall, Vince. Now I can either call an ambulance or take you myself.”

“I’m not going in an ambulance,” Vince says, his words slurred.

“Okay, it’s settled, you’re coming with me. We’re parked two blocks away. Can you walk that far?”

“Give me my money,” Vince says weakly

“You’ll get your money. Can you walk two blocks?”

Vince nods.

Charlie turns and faces her. She’s never seen this side of him, so assertive and clear, and now he offers her a kind smile. She’s amazed that in one breath Charlie is able to be both forceful and tender. “It’s going to be okay, Pina.” He points east. “I want you to walk over to Union Square and wait for me there. I’m going to drop Vince off at UC Med on Sutter and come back for you.”

Pina nods. “Take care of yourself, Vince,” she manages.

His face is bowed now in his fresh polka dot mask. He’s not showing his eyes. “Yeah, thanks.”

Charlie is back in less than an hour. The two of them take a walk on the streets around the square looking at the huge department stores: Macy’s Nordstrom’s, Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, artifacts from a lost world. Charlie takes her hand in front of Neiman Marcus and explains what happened. They checked Vince into the emergency after Charlie told them three things: that he’s a doctor, recently on the front line, who practically od’d in the Tenderloin, and ended up with a concussion. They wouldn’t let Charlie in, but somebody will call. He left a hundred dollars for them to give to Vince.

Pina stops walking in front of Neiman Marcus’s rustic spring window. It’s without the fresh flowers that must have been there before the closure. She faces Charlie. “What did Vince say on the ride to the hospital?”

“Not much.”

“He must have said something.” She can tell Charlie’s holding back.

He massages his chin between his thumb and forefinger. “He said he cracked nearly two months ago, not long after you came to Sonoma. He freaked out at the hospital and started going crazy with drugs. First with pharmaceuticals, and then . . . The thing, he said, that bothered him most was how he let you down.”

“He said that?”

Charlie nods.

She’s not going to let herself cry. “Did he say anything about you and me?”

“No.”

“What did you say to him?”

“I just listened.”

Before they walk to the car they grab a bench in the square and eat their ham and Swiss sandwiches. Again Charlie asks her if she is okay.

“No, I’m still in a state of shock seeing him like that.”

Charlie puts a hand on hers but says nothing.

At the car, he asks if she’d like him to drive. But no, she wants to drive. They sit together in front seat and he gives her just what she wants: silence. Just after the turn at Sears Point, in the long pasture across from the racetrack, cities of sheep with their lambs are grazing. She’d seen them on the way down. Now she pulls into a turnout.

“What are you doing, Pina?”

“I just want to have a look at these sheep.” She gets out of the car and walks fifty yards to a ridge with a good view of the pasture. There are hundreds of creatures down there, mowing the fields after the unseasonably late rain.

Charlie has come out and stands a short distance from her. Vince and the city seem so far away. Not really. She’s just screening off that tableau for a moment.

“Charlie,” she asks, “How does the arrangement work between the sheep keepers and the landowners? Who pays?”

He’s beside her now and drapes an arm over her shoulder. It is still an amazement, this touching another human being.

“The landowner pays, in this case Sears Point. And the people who bring out the sheep have their own fencing and usually a couple of sheep dogs, trained to discourage coyotes. The other benefit to the landowner is that sheep fertilize the land.”

“Oh, I was hoping it was just a neighborly arrangement.” She wraps her arm around Charlie’s waist and pulls him close. Sweetness. She could call him that. They stay a moment and gaze at the civilization of sheep. She’s trying to notice all the different types, if they are even types, and then she sees them. “Look, Charlie.” She’s pointing. “Black lambs. There are three, no, four black lambs down there. I didn’t see them at all and now I’m seeing all of them. I’ve never thought of black sheep in multiples nor have I been aware of black lambs. Black lambs. I guess it stands to reason that black sheep come from somewhere. I find it a real comfort that there’s more than one.”

“A secret society.”

“A proper black sheep doesn’t care much for society.”

“How long have you considered yourself one, Pina?”

“Hmm. All I can say is that even though I’m not young anymore, I find myself identifying with the black lambs.”

“Hello,” Charlie calls at the door.

“It’s open.” She’s drinking iced-tea, of all things. “In here.” She may have a glass of wine later with Charlie. “Oh no.” She can’t believe what she’s looking at—Charlie, in a turquoise wrestling mask and shiny black overalls, black leather high-tops, and a quilted pouch dangling from a shoulder strap. He leaps from the hall into the big room and lands like a gymnast, feet well apart, arms outstretched, the quilted bag swinging like a pendulum.

“I’d say you nailed it.” She claps her hands again; she can’t stop applauding for this guy. “Who are you anyway?”

“You don’t know?” He points to an ivory crown embossed on the turquoise. “This doesn’t give it away?”

Pina shrugs.

“Didn’t Vince give you an introduction to his most important masks? Yo soy Rey Mysterio, the Mystery King.”

“How do you do?” Pina folds her legs underneath her on the couch. “You know that mask offers absolutely no protection.”

“Why would I need it?” He beats his chest with his fists. “The lucha libre máscaras cover everything except the nostrils and mouth because the mightiest among us need no protection.” He stretches his arms out again and repeats, “Yo soy Rey Mysterio.”

“Have a seat, Rey. I know Mexican wrestlers never take off their masks, but . . .”

“No, no, I’d have to be unmasked. I have something for you.” Charlie/Rey Misterio pulls a plastic bag from his sack and extracts another wrestling mask. “It’s Xenia, I’ve always wanted to wrestle her.” He tosses Pina the mask, which feature an abstraction of horizontal lines.

“So you’ve come to wrestle,” she says, standing.

“That’s who I am.”

What a wonderfully funny fool of a man. Now she regards the mask skeptically.

“Nobody’s worn it. I just took it off the wall.”

Strangest fucking mating ritual she’s ever seen. Charlie’s quite a guide to alternative realities: first an African parrot that aspires to be human and who has a grasp of the facts of life, and now a tour of Mexican wrestling. Is it good that she’s sober or would she be better off bombed?

She quickly pulls the Lycra monstrosity over her head and drags it down her face. Now she’s smothered by it. At least it’s not as warm as she expected.

“Xenia,” he says, flashing her a big-toothed smile through his mask.

Is she really going to do this? Why the fuck not? Pina/Xenia makes a warbling echo in her throat. Yes, she can play his game, she thinks, as she rushes him. Before Charlie/Rey Mysterio reacts, she has him in a hammerlock, a move Corky Eichorn taught her forty years ago. She jerks his pinioned arm up high and waits for him to resist, but he doesn’t. So now he’s disrespecting her. No matter, one quick motion with her free hand and she peels off his disguise. “Ha,” she says, and marches around the fictive ring with her prize, going full Greek widow with her deep-throated warble.

Charlie’s hair stands up in a wild cowlick. “I should feel humiliated, but I’m exhilarated.”

Pina/Xenia continues to circle the big room, throwing her fists in the air and flexing her muscles. “Yeah, not so macho anymore.” His cowlick gives him the look of a man-child in serious need of a haircut.

“Aren’t you going to take your mask off?” Charlie asks.

She gets into a warrior’s crouch. “See if you can take it off.”

He rushes her. But what does he do? He insults her again, this time with a limp headlock. How do you to expect to strip off a wrestler’s mask when you have them in a headlock? She’s out of his hold in a jiff and slips behind him, bringing her forearm across his Adam’s apple. “We’re not playing here. Can you survive this?”

Apparently, he’s had enough. He breaks out of her hold like it ‘s a band-aid and digs his arm down between her legs, up against her bare crotch—so much for social distancing—and lifts her to his shoulder, yanking off her mask. Then he twirls her around the room several times before taking a crooked a path to the bedroom and letting her fall in a heap onto the bed.

“Now for the Plancha,” he says, and drops down on top of her, expertly managing his weight with his hands so that she doesn’t absorb any of it. He pins her arms down. “Uno, dos, tres.”

Pina is lost in the blue of his eyes. “My master.”

“Forgive me.”

“For what?”

“For imposing my madness on you.”

“I’ve enjoyed it so far. Let’s see what else you’ve got.”

All of her body is awake in a way it hasn’t been forever. He tugs on a hank of her hair and the follicles of her scalp tingle. She closes her eyes as he drops small kisses on her lids, and then on the bridge of her nose with a little trail to the tip.

“I love your nose.”

“Be careful,” she says, “It’s sharp and I’ve used it as a weapon before.” Her voice sounds husky to her. Has her warbling affected it? Or is this her new love voice?

Now the moment she’s been waiting for—he begins unfastening her buttons. She takes his face in her hands, rubs them pleasurably against the grain of his two-day growth, and then kisses him fully on the lips. She wants to know how well he multi-tasks. Oh my, his hands are on her breasts and the nipples respond at once, standing tall.

She opens a Sauv Blanc, and prepares a cheese plate with a very local Vella Mezzo Secco, and a soft Brilliat Savarin. She has no bread or fresh crackers so she breaks open a box of matzo she bought when it went on sale after Passover.

“Ah,” Charlie says, “Matzo in bed.”

“Yes, we’ll be nicked by hard crumbs all night, reminding us that we’re living in the middle of a plague.”

Still standing, she takes him in, all curled up like he belongs in her bed. She loves that Charlie’s a guy who’s comfortable with his body and who shares it nicely.

He props himself up with a couple of pillows. “And the matzo reminds us that we are like the Jews, making our bread in a hurry, well not that much of a hurry.” He shoots her a sideways smile.

The top of his hairy chest is a small joy sprouting above the quilt. Pina lays the tray down beside him on the bed and pours them each a glass of wine. She raises her glass to him. “Chin chin.”

He offers a singular Chin in return. “Also, the matzo recalls the Exodus.”

She climbs into bed beside him. “You’re really stuck on the matzo.”

“No, I’ve been thinking about this,” he says. Two cute worry wrinkles spread across his high forehead.

“The Exodus is a good corollary for our time, don’t you think? We all need to make the crossing from our old lives to the new, whatever that is.”

She spreads Brillat over a couple of pieces of Matzo and hands him one. “Have some manna from heaven.” She washes a big splash of the cold, dry wine around her mouth.

“Hmm,” Charlie says as he inhales the creamed matzo. He props himself up on an elbow. “The thing is, no matter what the Trumpites say, there’s no turning back on this journey, there’s no old life to return to.” Charlie pauses for a sip of wine. He holds up a finger to indicate that he’s not finished. “And the Exodus will not happen quickly. The Jews wandered in the desert for a generation ”

“Do you think our Exodus will take a generation? Will there be Golden Calves and a new set of Ten Commandments along the way?”

“Of course, the whole shooting match. Greed has a way of manifesting itself everywhere.”

“And there will be new doctrines?”

“Of course.”

She pours them each of them a fresh glass of wine. “You see I know all about the Exodus—I watched Charlton Heston in “The Ten Commandments” on TV when I was a kid.”

“Makes you an expert. Myself, I was always fond of the burning bush.”

She prepares another matzo for him, this one with the dry Monterey Jack. As he nibbles on it she drops a kiss on his forehead, but it doesn’t seem like enough, so she continues all the way down to his neck, riding the lump of his throat as he swallows the last of his Exodus matzo.

When their repast is finished, they make love again. “How can you do that, Charlie? You’re not twenty anymore.”

“It’s you, darling. You’re the inspiration.”

It’s clear that they’re not going to sleep much tonight. She falls off for a half an hour or so. Now she can say she knows what it’s like to sleep in Charlie’s arms. “Did you sleep?” she asks, rubbing her eyes.

“No, but I watched you sleep.” He kisses her again on the bridge of her nose. “You still haven’t used it as a weapon on me.”

“Just wait.” There’s only one thing she wants to do—shower kisses on his chest and slowly slide on down. “Look, Charlie,” she says, “I have a theory of my own: I believe I’d be happier in love during the great Exodus, than not.”

Charlie massages his chin between his thumb and forefinger. “The great Exodus and beyond. That’s the kind of theory that I can subscribe to.”

“But we’re only talking theory,” she reminds him.

Charlie burrows his nose into her neck. “I know. Let’s keep it that way,”

At noon they get out of bed and have their coffee on the deck. She’s done an excellent job of keeping any thoughts of Vince at bay. Neither of them have spoken of Vince. She turned off her phone before Charlie came and only checked it once in the night. There’d been no calls. But now when she goes to make more coffee, she feels the phone vibrate in the pocket of Charlie’s red flannel, walks to the second bedroom, and shuts the door.

Vince’s breathing sounds like that of a man who needs oxygen.

“Hello.”

“Pina. I got you. I must be blessed.” Vince sounds like he’s speaking in a room full of fog. She can hear the noise of the street—cars going by, voices, incoherent arguments.

“How are you, Vince?” She tells herself not to ask where he is, though that’s what she needs to know.

“Oh well, let’s not talk about me,” he says, and laughs, and then chokes a moment on his laugh before corralling it. “It’s the same old, same old with me. I’m down here with the strange people. If you ask them what time it is, they say, ‘Night time.’ And that’s during the day. You’ve got to mind your P’s and Q’s down here. Do you know that expression, Pina? You should, you’re a drinker. It pertains to pints and quarts, but let’s leave it at that. I don’t know why you brought that up. So any-who,” he says, drawing out the word in a sorry imitation of his debonair self, “I have a situation here that’s troubling me. I’m temporarily out of cash. Things are not as liquid as I’d like. What would be nice, what would be really nice, is if at your earliest possible convenience you could bring me some cash, that would be tip-top and I would be eternally grateful.”

She can’t keep herself from asking him where he is.

“Well that’s the thing. Where I am and where I will be are very different matters.”

“Can you give me a street corner?”

“Let’s just say Leavenworth and Eddy, though I stay away from street corners. That’s where bad things happen.”

She takes a long breath. “I can meet you there, Vince. Leavenworth and Eddy, but not at the corner. Give me two hours and I’ll be there.”

“Two hours, huh? Two hours is a long time out here. Are you getting your nails done, Pina?”

“I’ll see you in two hours, Vince,” she says and ends the conversation.

Back out on the deck, Charlie has a big grin on his face. “Pina, Pina,” he says, “look what I’ve found.”

He’s still seated where she left him. Pina goes to him and wraps an arm around his shoulder. He has ladybug perched on the middle of his left thumbnail.

“She’s been sitting here the whole time you’ve been inside. That’s a lot of good luck. Put your hand out here. Let’s see if she’ll transfer to you. That would make for double good luck.”

“But what if she flies away?”

“We have to live dangerously, Pina.”

“Won’t that spoil your luck?”

“My good luck has already been made with you. Open you hand.”

She offers her hand and brings his thumb to meet, gently spilling the orange bug into her palm where it rights itself and settles.

“Good luck abounds,” says Charlie.

Pina wants to cry, but forces a smile instead. “Funny, I’ve been collecting all manner of creatures since I’ve been up in Sonoma. Maybe they’ll come along on the Exodus.”

She notices Charlie’s empty cup. “Oh no, I’ve forgotten all about the coffee.” She manages to pass the congenial ladybug back to Charlie. “Be right back.”

She’d rather not tell Charlie about Vince, but she has to. Over coffee she has to tell him.

“I just started driving. I had nowhere to go, but I went driving.” It’s Vince, calling early.

“Are you driving now?”

“I feel like I’m driving, but I’m not.”

She props herself up on her pillows. It’s a quarter to six. He sounds scared, maybe disoriented. “Are you okay, Vinnie?”

“Not so much. I think I’m loosing it. I’m all bled out. I should go off and die in the woods like an old wolf.”

The urgency in his voice forces her out of bed. “Tell me what’s going on, Vince. Talk to me now. Is it really bad at work?”

“I don’t want to tell you. You don’t need to hear about that.”