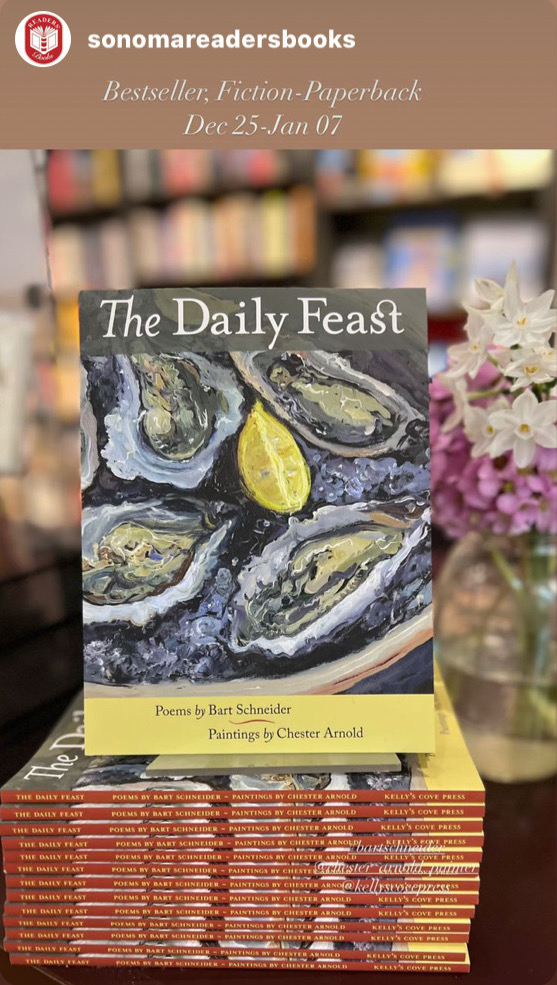

We’re thrilled at the audience reception for The Daily Feast, which won the title of “Bestseller – Fiction – Paperback” at Readers’ Books in December. Thank you Readers’ for your support of our small press!

We’re thrilled at the audience reception for The Daily Feast, which won the title of “Bestseller – Fiction – Paperback” at Readers’ Books in December. Thank you Readers’ for your support of our small press!

Chinese-born American artist Hung Liu, an Oakland-based painter internationally recognized for her work exploring notions of identity, immigration and the Maoist culture she grew up in, has died just as her latest exhibit went on display at San Francisco’s de Young Museum.

The cause of death was pancreatic cancer, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco confirmed Saturday, Aug. 7. Liu was 73.

“We are deeply saddened by the news of artist Hung Liu’s sudden, premature passing and our thoughts go out to her family at this difficult time,” officials at the Fine Arts Museums, which include the Legion of Honor and de Young Museums, said in a statement. “A vibrant and vital part of the artist community in the Bay Area and beyond, Liu’s impact as an artist and as a teacher are profound. A trailblazer among Asian American artists, the legacy and extensive oeuvre she leaves behind will continue to advocate on behalf of the people who have come to our country and helped build our nation.” …read more at sfchronicle.com

August 7, 2021

Kim Sajet, Director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, issued the following statement on the passing of Chinese-born American painter, Hung Liu, ahead of the museum’s upcoming exhibition “Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands,” the first major presentation of Liu’s art on the East Coast:

“The National Portrait Gallery mourns the death of Hung Liu, whose extraordinary artistic vision reminds us that even in the midst of despair, there is hope, and when people help each other, there is joy. She believed in the power of art—and portraiture—to change the world.” ….read more at npg.si.edu

Artist Hung Liu is creating an installation for Wilsey Court, the first exhibition space visible as you enter the de Young Museum. Golden Gate will combine new work with existing work, and explore themes of international and domestic migration. For more information visit deyoung.famsf.org.

Hung Liu: Golden Gate

William T. Wiley — a founder of the Bay Area Funk art movement who expanded into every medium and style of creation from watercolor to printmaking to giant sculptures in a career that lasted from 1960 until just a few months ago — died Sunday, April 25, at Marin General Hospital.

His death was due to complications from Parkinson’s disease, which he’d suffered from since 2014, said his son, Ethan Wiley. He was 83.

A painter with a unique style developed at an early age, Wiley had exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1960 when he was 23 and still an undergraduate at the San Francisco Art Institute. Since then, SFMOMA has come to own 50 of his pieces, with eight of them — in mediums from ink on felt and leather to etching on paper — on display in a designated gallery since the museum reopened in March. Read more at datebook.sfchronicle.com…

The front page of this week’s East Bay Express features Kelly’s Cove Press and our most recent title Ghosts: Seventy Portraits, a selection of portraits from Oakland-based painter Hung Liu. Read it HERE

The front page of this week’s East Bay Express features Kelly’s Cove Press and our most recent title Ghosts: Seventy Portraits, a selection of portraits from Oakland-based painter Hung Liu. Read it HERE

I can’t believe what I saw: Vince, who’s just crossed the street, says some shit about the dead rooster killed by the dog, that Gus, here, in the vegetable shed, has been yakking about. I don’t hear the words clearly, but they set Charlie off. He lurches toward Vince, who’s backing up. Doesn’t say a word, but clocks him. The chillest man I’ve ever known floors the most arrogant with a single blow.

My first reaction is exhilaration, I’m ashamed to say, like some honky-tonk chick in a B movie, who’s got two guys going bare-fisted over her. I can see it all from the shed: a large-headed white woman screaming at Charlie as he walks away without a glance toward me, like we didn’t walk over here together to get vegetables; and Vince, on the dusty ground in his striped pants, talking himself into sitting up, beside a couple of fallen breadfruits.

I’m not ready to go out there. I move from the squash to the potatoes and start dropping good-sized russets with dirty faces into my sack. Gus, who, since we met in May, has taken a perverse pleasure in calling me Pita, rather than Pina, has the same idea as I did: “So you got your boyfriends fighting over you, Pita. Nice trick.”

I don’t respond. I keep dropping potatoes into the sack. When I’ve collected about twenty, Gus says, “What’s the deal here, Pita, are you buying all those potatoes or are you playing some kind of counting game?”

Why be offended by a geriatric sot, plopped on his ass ogling and disrespecting me?

“I’m buying them, Gus, unless you have a limit per person on russet potatoes.”

“They’re all yours, Sis.”

I plop more potatoes into my bag.

“So what are you going to do with all those taters?”

“Throw them at men I don’t like.”

“That’s a lot of men.”

“Some guys will get multiple potatoes, Gus.”

“Good thing you like me.”

“I might not waste a potato on you.”

I pile them up on the counter in front of Gus and watch as he struggles to get them all on the small scale, in fours and fives. When a couple of them slide off the scale and hit the ground, he gets all flustered.

I say, “You’re not used to potato-tossing women, are you, Gus?”

“You’re crazy as a loon, Pita.”

Vince is on his feet by the time I haul my twenty-three pounds of potatoes out of the shed. He’s taken off his mask and used it to wipe blood from the corner of his mouth.

“What you got there?” he asks.

I keep walking, taking lurching steps with my heavy load.

“Not getting a whole lot of love from you and Romeo,” Vince calls after me. “Why not come over to my pad and give me a little comfort, Pina?”

“Fat chance.”

“Tell Romeo that he’s got his coming.”

Once I haul the potatoes up the steps I drop them on the concrete landing to make a hearty boom. This brings Charlie to the door with a grin on his face.

“What was that all about?” I ask.

“It wasn’t premeditated.”

“Does that mean whenever the instinct strikes you, you’ll slug somebody?”

Charlie has lost his grin; instead he’s studying me. “Are you coming inside?”

“You done hitting people?”

He gazes down at my sack. “I see you bought a few potatoes.”

“I’m going to make latkes.”

“For the whole neighborhood?”

“I looked up latkes on the Times website; they have twenty-one different recipes.”

“And you’re going to make them all?”

I enjoy that neither of us answers the other. It’s a curious duet, like our relationship—a partita of unanswered questions.

“Is it cultural appropriation,” I ask, “for a gentile to make latkes?”

Charlie pulls the door open wider. That’s as close as he’ll get to truly inviting me in. I’ve made an executive decision: I’m not picking up the potatoes again—twenty-three pounds of brainless spuds plopped there in the cloth sack. I gather the mouth of it and drag the sack, humpty-dump over the threshold, into the hall and then across the wood floor, straight to the brick fireplace. The firewood is stacked, nobly in its rack, on the other side of the gaping black mouth. I spill out the humble potatoes, in twos and threes, and decide to make a small mountain of them. Charlie watches with his mouth open. Does he, like Gus, think I’m crazy as a loon? I stand back from the pile. Seen from a distance it might represent an entire civilization. Some freckled and misshapen, some with random eyes and sharp chins, this pile of brown roots most certainly predates us.

I get a call from Sally, who sounds more than a little bonkers. At least she gets down to business: “We need to do an intervention on my dad, Pina.”

“What’s he done now?” I ask, trying to bring a measure of levity to the conversation.

“This is no time to jest.”

“Who’s jesting?”

“I mean if you’re like in an oppositional state, Pina, I’ll find another ally.”

I hear the revved motor behind Sally’s voice; her mind’s running a mile a minute. “What’s the issue?” I ask in a flat voice that cannot be misconstrued.

“It’s an abdication . . .”

Is the poor girl referring to royalty? Has she just begun watching The Crown?

“A dereliction of duty.”

“What duty?”

“Charlie’s responsibility to Roscoe.”

“Has he not been feeding the parrot?”

“I think you’re purposely being oppositional, Pina.”

If she keeps saying that word I’ll take it as a suggestion. “I am not. Please explain.”

“Charlie has allowed Roscoe to go dormant, missing in action, right when we need him most. The Electoral College electors have confirmed Biden’s victory. Mitch McConnell has congratulated Biden and called on his fellow Repugnants to ditch their fraud conspiracy nonsense; the Georgia senate races are looming; cabinet appointments are being made, and where is Roscoe? We need his pithy statements, his wisdom, his joy. We can’t go on with this radio silence. Charlie has built a brand just at the point of taking off; now is the time to capitalize.”

Capital sounds like the key word. Sally is seeing dollar signs. At the risk of sounding oppositional I ask, “What if Charlie isn’t interested in perusing the brand idea?”

“Then he’s a fool,” his daughter says.

“Shall I relay the message?”

“You’re not useful at all, Pina.”

“Funny, I’ve been told that before.”

The conversation ends abruptly as Sally hangs up on me.

Tonight I make latkes for the second time, box-grating the potatoes in hopes they’ll be less like the Cuisinart-shredded taters of last night, which came out a bit like hash browns. I use Florence Fabricant’s recipe with four eggs and fifteen ounces of ricotta cheese. It makes forty small latkes and Charlie and I manage to eat thirty-one of them. We have apple slices, caramelized marvelously in butter after a slow sauté in Charlie’s copper skillet, and figure with the near-pound of ricotta that we don’t need a side of sour cream.

“As it is,” Charlie says, “our cholesterol readings are off the charts after two nights of latkes.”

“Do you think we can trigger simultaneous heart attacks?” I wonder. “We’d be inventing a new form of double suicide.”

Charlie’s expression turns thoughtful. “Death by latke. Have another one, Pina.”

I comply but when I ask Charlie to join me he demures. “Oh, so you want to watch me die.”

Then Charlie turns grim. He says he thinks we might all die given the way the virus is exploding and how many dumb yahoos in this country are still in COVID denial. “There’s guys on their deathbeds,” Charlie shouts, “unwilling to admit that it’s the virus that’s killing them. They want it to be cancer so bad.”

Charlie trots out numbers: 251,000 cases a day and 3,330 deaths. He tosses his hands in the air, exasperated. “I remember back in the summer, when we had 50,000 cases a day. Dr. Fauci said, ‘If we don’t wear our masks and avoid parties, we may see 100,000 cases a day. That forecast was shocking. Look at us now, we’re two and a half times that, and the Christmas disaster is right ahead.”

Over a salad of little gems and radicchio, with a sharp vinaigrette, I steered the conversation to the merits of each style of latke. Surprisingly we agreed that the first night’s latkes were the superior. “Both crisper,” Charlie says, “and more succulent.”

Next I tell Charlie about my conversation with his daughter.

“I think Sally’s using,” he says, “and I don’t know what to do about it, so I do nothing. That’s what Al-anon would recommend.”

Charlie’s head dips toward the table and I find myself looking at the bald spot in the center of his skull; it’s widened significantly since I’ve known him—the perfect year for a man’s hair to fall out. I reach over and grab Charlie’s hand.

If it weren’t for the virus,” he says, “I might be tempted to get in there and try to help Sally sort things out, and would probably fuck things up further.”

“Well, just so you remember that it’s Sally who wants to do an intervention on you.”

“And you weren’t tempted to help here?”

“Hmm. I might, you know, if you get too deep into the Roscoe branding thing.

Charlie rolls his eyes. “I could give a shit about the branding, but I agree with her that I should be utilizing Roscoe to get certain messages across—I’m just not sure what the messages are.”

I have nothing to add and, in a rarity for me, I stay quiet. When I am ready for bed, Charlie says he’ll come a little later—he wants to do some work with Roscoe.

When I leave the bathroom after brushing my teeth, I see Charlie’s torso bent over the kitchen sink. I mean to give him a goodnight kiss, but he’s eating persimmons. His friend Arrow left a supermarket bag full on the doorstep. We’ve been watching a bowl of them ripen on the kitchen table. I like how they look, but I no longer consider eating them. We used to throw them at each other as kids.

One night Charlie described the tree in Arrow’s backyard. “It’s absolutely bare, except for these exquisite fruits hanging like ornaments, with their smooth-faced gloss and otherworldly pigment. Standing underneath that tree when it’s in full bloom, I feel like I’m living inside a Persian miniature.”

At the sink, Charlie looks like he lives inside a persimmon itself. He’s halved five or six and is sucking the muted orange slime from the overripe halves, with absolute abandon. Polyps of gooey fruit stick to his face and drip from his chin into the sink. This, somehow, is the man I love.

A common nightmare wakes me. I’m trying to get home but always take the wrong alleys and stairways; I get so tired of the circuitous trails and flights of stairs that I wake myself and am glad to be here.

Charlie hasn’t yet come to bed. Certainly he’s finished slamming persimmons. I put on my kimono and creep over to Roscoe’s room. Charlie is instructing the parrot to project his voice. “Let it boom, Roscoe, let it boom.” Charlie’s forceful voice demonstrates what he means.

I stand a distance from the closed door, but I hear them well. Charlie has come up with some bad rhymes that evidently go over well coming from the mouth of a parrot.

“Roscoe here. I’m going to be terse, it’s getting wertz.”

“The word is worse, Roscoe, worse.”

“Wertz, wertz,” the bird says.

Charlie, ever patient and encouraging, says, “Listen closely now with your mighty parrot ears: worse, worse.

After several more attempts, Roscoe nails it.

“Bravo. Kudos. Praise be to you, Roscoe. Now, let’s take the message from the top.”

“From the roof, Charlie?”

“Yes, from the roof, and try to take it all the way through the end of the message.”

I still don’t believe that it’s a parrot doing the talking, coming up with metaphors and all the rest, and yet the alternative is more frightening. What if Charlie is responsible for both voices, tossing the alternate voice, like a ventriloquist, from one side of the room to the other, in a faux training session behind closed doors? Talk about an alternative reality. How far is this practice from hallucination and madness?

“Okay, here goes nothing, Charlie,” the voice of the parrot says, “Roscoe here: I’m going to be terse, it’s getting worse. Forget defiance, believe the science.”

“Excellent job, Roscoe. First rate.”

“Top notch, Charlie?”

“Indeed. Now let’s try it over again.”

I become weary while leaning against the wall, and soon I slowly slide down it, curl into a ball, and sleep. When I awake, who knows how much later, man and bird are still at it, now with a new message: “Roscoe here: I need to share it, you’ve got to wear it.”

Awake now, I want the parrot to depart, like the noxious qualities of a dream, like the coronavirus itself, but the bird’s voice rings out again, as if to address me directly: “Roscoe here: I want to be crystal clear, the virus isn’t going to disappear.”

I made a birthday cake for Charlie today, a horribly misshapen pineapple upside down. It looked like it was going to explode at the sides and collapse. After buying two packs of mini birthday candles I decided to tempt fate and puncture the surface fifty-nine times. Charlie closed his eyes before blowing out the candles. I knew what his wish was and didn’t mind that I wasn’t included in it. Cutting the cake required surgical precision. Charlie asked for a small slice and I had the same. At that rate of consumption, the damn cake will last two weeks. It wasn’t bad, certainly better than it looked and, in the gloom that followed our attempt at festivity, I imagined stuffing the remainder of the cake in hearty hunks down the toilet.

Charlie had assumed the faraway look in his eyes that I’d first noticed after he turned Sally out of the house. It was as if a spell had been cast over him and I saw little chance of breaking him out of it, not that I really tried.

Earlier, before dinner, I asked Charlie to bring Roscoe to the table with us—that way, I thought, he’d have his group of three. Charlie obliged, leaving the parrot in his cage beside the table on a rolling tea tray. It seemed that Roscoe sensed the oddity of the situation. He spoke sparingly, but practically everything he said unnerved me.

I’d done a couple of fat, highly peppered filets on the stovetop with a flambé of cognac, along with au gratin potatoes and out of season asparagus from Mexico. Roscoe ate sparingly from a small bowl of seeds, nuts, and dried rosebuds that Charlie saved for him. After demolishing a bud, Roscoe addressed me directly. “A rose by any other name, Pina, would smell as sweet.”

I watched Charlie, as the parrot spoke. I still suspected ventriloquism but Charlie’s lips didn’t move a hair. “Have you been reading Shakespeare?” I asked the bird, after I regained my composure.

“I wish I could read,” Roscoe said, wistfully, or so I imagined. “Charlie reads to me and plays recordings.”

“You aren’t eating, Roscoe,” Charlie said. “Is something the matter?”

The parrot looked thoughtful and then he said, “I’m sated, Charlie.”

Roscoe’s speech was seriously freaking me out. It wasn’t just what he said, but how perfectly he’d mastered the tenses, and knew the appropriate thing to say at any given time.

“Did you teach him all this, Charlie?” I whispered.

Charlie shook his head. “I did at first, but now he’s on his own.”

“It’s not possible,” I said, full-voiced. “This isn’t real.”

“I’m afraid it is, Pina.”

Roscoe made a couple of peck-peck sounds and nibbled on a dried rose petal. Then with his head perfectly still, his eyes roved from me to Charlie. “I’m sorry to interrupt your party, Charlie. If I could I would take my leave.”

“Say goodnight to Pina, Roscoe.”

The parrot nodded his head. “Bonne nuit, Pina.”

Charlie lifted the cage and walked the bird to his spot in the second bedroom. I cleared the dishes and brought out small plates for the homely cake. When Charlie returned to the table I went out to the kitchen, lit all the candles on the cake, and brought it to Charlie, forced out a boisterous version of “Happy Birthday.” We sat and looked at the cake a moment, with its wide swath of burning candles. It reminded me of images I’d seen on TV of the new fires burning in Napa and Sonoma counties. That’s when Charlie closed his eyes, made a wish, and blew out the candles.

I could tell that he didn’t want to talk about Roscoe anymore, and the implications of having a genius parrot that could speak and reason as well as a bright human. Instead, Charlie told a story of a birthday party he had more than fifty years ago.

“I was seven-years-old that day. My mother prepared a box lunch, in an actual box with a folding lid, for six of my friends and me. Each kids’ name was written in huge block letters on the lid of the box.”

“How do you remember all that?” I asked.

“It was a memorable day. I was very proud of the boxes my mother made up. Each had an egg salad sandwich on white bread, a tiny box of raisins, a small bag of potato chips, a huge chocolate chip cookie, a napkin that said: HAPPY BIRTHDAY, and an assortment of party favors. I have a photo of that party which has helped me keep the memory fresh.”

“How often do you look at the photo, Charlie?”

“Every ten years or so, but here’s the thing: of my six friends, five were boys. The girl, Rosalie, lived across the street and went to the Catholic school, St. Bart’s, while the five boys went with me to Maxwell Cubbins Elementary. Rosalie was actually my best friend, but I didn’t want the boys to know that. She had five older brothers and was one hell of a tomboy, much more daring than me. Rosalie taught me a lot of things that a boy should know how to do, things she learned from her brothers, like how to whistle and tie a slipknot. She’s the one who showed me how to make a reliable slingshot. She carried a pocketknife with a buffalo on it and we took turns carving our initials on trees and fences.”

“Did you carve your initials inside a heart?” I asked.

“No, no, it wasn’t like that.”

“Don’t worry, Charlie, I’m not jealous.” That got us both chuckling. I had no idea where this shaggy dog story of Charlie’s was heading, but it was clearly taking us far from Roscoe.

“The boys at the party wouldn’t talk to Rosalie so I didn’t talk to her either.”

“Typical.”

“And when we started to eat our lunches, all the boys began with our cookies, and made fun of Rosalie for eating her sandwich first. That’s when she choked on a big gob of sandwich. We were gathered around the breakfast room table, and my mother hung back in the kitchen, watching us from a distance. Rosalie sat directly across the table from me and I could see that she was choking. I called for my mother. This was before the Heimlich maneuver was part of the culture. My mother ran over and slapped Rosalie hard on the back a couple of times and she finally coughed up the big chunk of sandwich.”

Charlie gazed at me a little sheepishly before continuing. “Artie Bosco, who sat next to Rosalie, and had pulled his chair as far from hers as possible, as if she had the cooties, said, “Geeze, Rosalie, you got to chew your food.” She stuck out her tongue at Artie and just then he noticed the floor beneath her, and screamed: “Look, look what Rosalie did.” The other boys and I dashed over to witness the puddle she left on the floor. Poor Rosalie lashed out with both her arms and scooted out of the breakfast room and on out the front door.

“Later,” Charlie said, “when I was in bed, I remembered the look in Rosalie’s eyes and, for the first time thought, it must be harder to be a girl.”

I had the feeling that Charlie made up his birthday story from whole cloth. I was impressed with all the details, and yet if there’s anything I’ve learned about Charlie, it’s that he’s a detail man. But what seven-year-old boy has that kind of insight—that life must be harder for a girl? Did Rosalie actually leave a puddle of pee on the floor? Did a girl named Rosalie even live on Charlie’s block? Was the whole idea of the box lunches a fabrication? I didn’t press him on the veracity of his story. Once he told it, more than likely as a diversion from Roscoe, it became part of his past, just as an improbable dream does.

Of the new fires, the Glass Fire is closest to us. It has blazed over the Mayacmas from Napa Valley, where it destroyed numerous wineries and houses, all the way to the east end of Santa Rosa, and across Highway 29 into the retirement community of Oakmont, which evacuated all 4500 of its residents. Charlie and I watched on the news as the oldsters from the Oakmont assisted living facility lined up with their walkers outside at 11PM. Many were in their bathrobes, waiting for the next bus. One old woman in a wheelchair held a teddy bear in her lap. Charlie teared up as we watched because his mother had moved down to Oakmont, to be close to him after his father died, and she spent her last days in Oakmont’s assisted living facility.

“She loved it there,” Charlie said, “particularly in the dining room. She sat with her friends at a big table and the Latino waiters flirted with the old ladies as they recited the choice of entrees and asked if they’d like another scoop of ice cream. My mother said it felt like they were on a cruise. That was before cruise was a dirty word.”

The fires are still a long way from the town of Sonoma but the smoke is bad and getting worse. Charlie and I talk about where we could go and never come up with a solution, even for the short term. It’s gotten smoky out at the coast. Deciding where to live is becoming an existential quandary for many Californians, and it’s extending beyond the state and across the entire west coast. Charlie says, that with climate change, Northern California will eventually become a desert; fires will have less fuel and no longer be so widespread. I don’t think we have the time to wait for that, and I’ve never fancied living in the desert.

Tonight, before we sat down to watch the first presidential debate, I told Charlie about an article I’d read about five African grey parrots in a wildlife park north of London. They egged each other on with vast vocabularies of swear words. Park goers loved it and swore back at the parrots, but the directors of the sanctuary removed the birds from public view because they were concerned for children who might get caught up in the crossfire of obscenities. Charlie got a good laugh out of that. Telling him about the “potty-mouthed parrots,” as the article worded it, was my way of letting him know I now understand how remarkable these birds can be and that I will be more accepting of Roscoe.

Charlie was in a good mood because he’d had a congenial conversation with Sally earlier in the day. She’d called to apologize for her behavior the other night. She told him that she was safe and very much looking forward to moving into her new apartment, the day after tomorrow.

“I have hopes for her,” Charlie said. “I’m glad she’ll be nearby, but not here.”

Neither of us was prepared for the craziness of the so-called debate. Charlie and I have been alternately repelled by the news. First I needed to have a moratorium, then he, now me again. I had to walk away from the TV thirty minutes after the debate started, but Charlie seemed to get a kick out of the debacle. He kept shouting from the couch: “Trump’s killing any chance he had.” “Biden just said, ‘Will you shut up, man?’” “Trump won’t condemn white supremacy.” “Biden called Trump a clown!” I finally went back to the couch and sat beside Charlie for the duration since there was no getting away from it. Instead of watching the television, I watched Charlie. “Trump’s cooked his own goose with this performance. How do you think his ‘suburban housewives’ are enjoying this?”

I heard my nonna’s voice coming from outside my childhood home, and rushed from my bed to the window. She stood beside a disorderly silver maple, dressed in her black widow garb, except for an uncharacteristic straw hat, ringed in faux cherries. I threw on one of Charlie’s flannel shirts but didn’t bother buttoning it. Down two flights of stairs to the street took an eternity. I could still hear her voice—it was all its verticality, climbing up and down the laddered rungs of her throat.

She sang out in spiky Italian: Il mondo sta volgendo al termine, the world is coming to an end. I put on a mask at the front door. Charlie is always making new ones, this one from a print with cherries and their stems. Sometimes the world aligns in harmonic convergence. This must be one of those times.

When I reached the street, my nonna was nowhere to be seen, but Charlie’s daughter Sally stood under the silver maple with a colander filled with wet, glistening cherries. A blood-red scar of cherry juice spread like a birthmark across her face. She kept shoving cherries into her mouth and spitting out the seeds.

“Have you seen an old woman?” I asked.

“I haven’t see anybody. I keep to myself.” Sally wiped her mouth with the back of her hand and now it, too, looked like a great wound.

“It was my nonna,” I said, “my grandmother.”

Sally spit out some seeds. “How old is she?”

I stopped to do the math. “One hundred and fifteen.”

“She must be on a salt-free diet and mainlining Vitamin D. I know for a fact that she’s ingesting plenty of fiber.”

Apparently, Sally had eaten enough cherries because she now picked them out of the colander and began throwing them at passing cars.

I was overcome with sadness at the prospect of not seeing my nonna again, and decided to go back in the house, but when I turned from the street, the house was gone.

Sally’s scream woke me. Charlie had already left for his early morning walk. When I got out to the living room, Sally was pacing back and forth, barefoot in flannel pajamas, mumbling to herself. I caught her eye and asked what the matter was. She looked back at me as if I should know. “That bird,” she said finally.

“He scared you?”

“Well, yes. I woke, sat up in the futon, and that bird said, ‘Top of the morning to you,’ in a fucking Irish brogue, and when he saw me freaking out, he said, ‘Is everything copasetic, dear?’ in a voice that sounded like my Aunt Emily’s. That’s when I screamed. Sorry about that.”

“No worries. Yeah, your dad’s really got Roscoe trained to say all kinds of shit. It is pretty spooky.”

“How can a bird do that?”

“Ah, now you’re asking questions too deep for me to answer. You know the person to ask.”

I brewed a pot of coffee and Sally and I sat apart from each other out on the deck. The fog had come in and it was nippy outside. I want to help Sally feel comfortable, not just about Roscoe, but about staying in her father’s house, with me around. That will be a trick because it’s not something that I’m comfortable with.

I gazed into Sally’s pretty moon face and the fetching gap between her front teeth. Her coloring is much darker than Charlie’s, and yet I can see a likeness around her eyes. As I sipped my coffee, I tried to imagine what it will be like for her to start over in the middle of a plague, and found myself thinking about the mess I was after Marco, my late husband died.

Sally smiled at me. “Where’d you go?”

Her question surprised me. It wasn’t as if we were in the middle of a conversation.

“You don’t have to tell me, but I noticed your mind take off on a jet and fly from one hemisphere to another.”

I shook my head. “You could see that? Are you clairvoyant, Sally?”

“Hmm,” she said, cryptically, before changing the subject. “Hey, I can tell that you’re good for my dad,”

“How so?”

“Well, for one thing, I haven’t noticed him smile so much in years.”

“I think he was just glad to see you, Sally.”

“Nah. He seems younger and like he’s got some kind of purpose.”

“His purpose is Roscoe.”

“Why don’t you want to believe what I’m telling you. Pina?” she asked, as if she were the elder.

“I don’t know . . . it makes me bashful.”

Sally laughed at that.

“What? Am I too old to be bashful?”

“Shush. I see the way the two of you look at each other. ‘Nuff said.”

“Maybe we were just putting on a show for you.”

Sally shook her head, as if I were hopeless. She finished her coffee and stood. “It’s time for my yoga practice. I want to see what that bird has to say when I stand on my head for fifteen minutes.”

“I can bring him out to the living room.”

“No, no, I need to make peace with Roscoe.”

I stayed out on the deck until Charlie returned from his walk, musing about the idea that somebody might love me, and my resistance to it.

This morning Sonoma is the second coming of Pompeii—flakes of ash falling from a yellow orange sky. We saw images of San Francisco in complete darkness at ten in the morning. In Sonoma the air quality reading was surprisingly decent. Apparently the smoke had risen very high in the atmosphere. A layer of marine air (I think that means fog) served as a buffer.

Charlie and I walked to the square. People carried on as if all this was normal. Deliveries were made to restaurants operating at quarter capacity. Tourists window-shopped in their masks. When weirdness becomes the norm you either roll with the punches or go mad.

It’s been two weeks now since Sally’s moved in. Charlie and I have danced around the inconvenience and we both know something has to give. The condo is too small for three people and a parrot in the middle of a plague.

Charlie took my hand and led me over to the duck pond—the site of our first meeting. We sat on the same bench, but no longer six feet apart. A single mallard glided around the pond and Charlie commented on him: “Everybody is a little lonely these days.”

I agreed. Since Sally moved in, I’ve felt unbalanced in a way that reminds me of loneliness. Lonely in a crowd. I asked Charlie how his work with Roscoe was going.

“I wouldn’t call it work,” he said.

“What would you call it? You’re in there with him for eight hours a day.” I didn’t like how that came out; it sounded so bitchy.

Charlie offered a thin-lipped smile. “Roscoe has an insatiable appetite for language.”

“So you’re feeding him words eight hours a day.” That too sounded bitchy. I couldn’t help myself.

Thankfully, Charlie changed the subject. “I’ve rented an apartment for Sally in Sonoma. It’s a really nice place, down on Broadway. I haven’t told her yet. I wanted you to know first. The problem is she can’t get in until October first.”

“That’s three more weeks. Maybe I’ll move back into Vince’s condo until she moves out.”

“Or I could take a driving trip with Sally,” Charlie said. He had a skeptical look on his face as the idea of the driving trip unfurled. “Okay, let’s see, because of the fires you can’t drive north, can’t drive south, and west you have the Pacific Ocean.“

“Sounds like you’re heading east young man, with your girl and your parrot.” Somehow saying this set us both off laughing. I hadn’t laughed so hard for a long time, not in modern memory, and the unspoken tension between Charlie and me lifted at least as high as the marine layer.

Sally was thrilled to hear the news about the apartment Charlie rented for her and said that she’d be happy to cook dinner. I didn’t look forward to the prospect and ended up chiding myself for assuming that whatever she cooked would resemble hippie chow.

I wasn’t far off. Sally made an African peanut stew that was moderately palatable. Along with a preponderance of peanut butter, she added sweet potatoes, brown rice, and collard greens from her garden. Before leaving the Lost Coast, she filled the back seat of her car with her harvest, and we are still in possession of more collards and kale than any three people could eat in six months. This dish was definitely stick to your ribs type fare, but I’m not sure whether my ribs will ever be the same.

“Any ideas for a wine pairing?” Charlie asked.

I suggested the heartiest red in Charlie’s cellar but Charlie doesn’t have a cellar and the only decent red we had on hand was an Oregon Pinot, which didn’t have nearly the tannin or starch to stand up to the stew.

Charlie, compensating for my polite response, was full of compliments for Sally’s dinner.

“Sally never used to cook,” he said.

“I cook all the time now.”

“Remember how you’d say, a contemporary woman should not spend any time cooking, because that reinforces the stereotype that a woman’s place is in the kitchen.”

“Yeah,” Sally said, shrugging, ”I said a lot of stupid shit, but at least there was some logic in the thought.”

“So you’ve evolved,” Charlie said.

“Or devolved.” Sally aimed a fat forkful of peanut stew into her mouth.

Charlie smiled at me and at his daughter. He clearly looked like a happy man. And, yes, I am beginning to believe he loves me.

Sally blotted her lips with her napkin. “I think we should do raw tomorrow night. I’m thinking a raw vegan lasagna.”

Neither Charlie nor I responded and I sat there trying to come up with the perfect wine pairing.

“Or should we do broccoli balls and cauliflower rice sushi?”

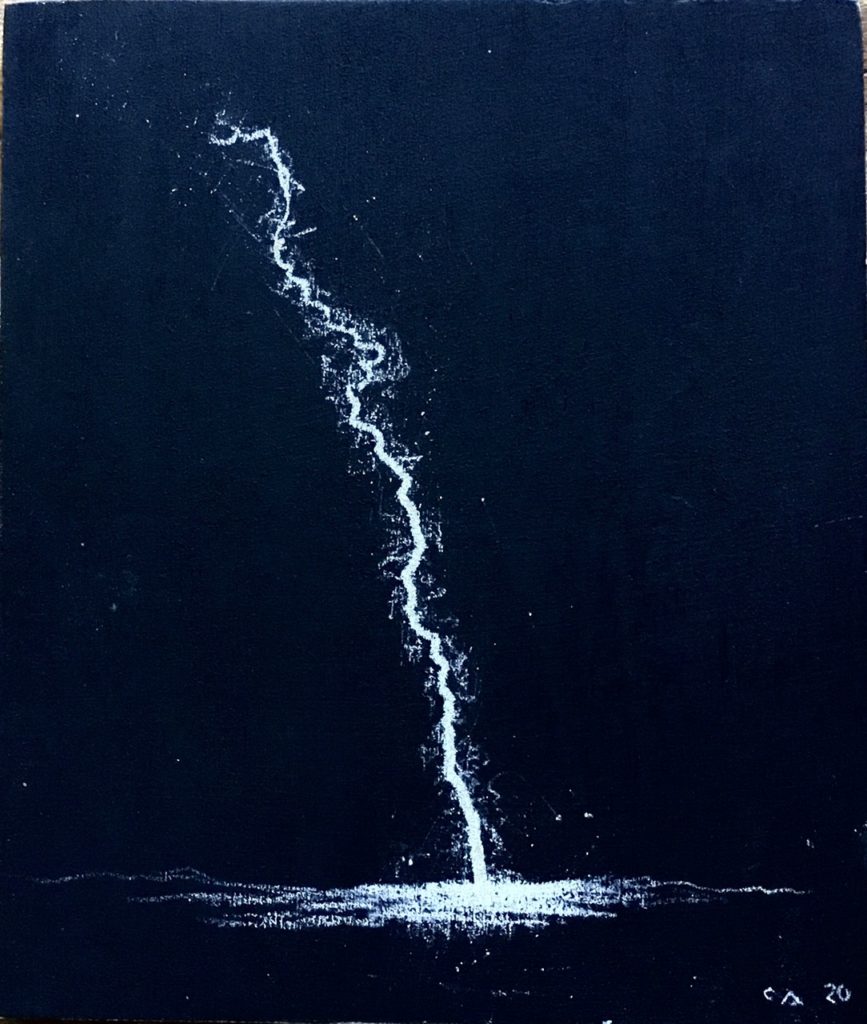

On Monday, Charlie and I took the morning off and headed to the ocean. The heat in Sonoma has been brutal, with the addition of something we rarely have: high humidity. We saw the pulses of dry lightening and heard thunder, the night before. The little bit it rained didn’t correspond with the lightening strikes, so numerous fires broke out.

We studied the skies as we approached Muir Beach on Monday. To our north, a stark black swath of sky was divided, by a line as hard as the horizon, from the mottled overcast sky above us. We guessed we were in the clear and lugged our blanket and cooler, filled with enough picnic fare for a big clan, onto the beach. We saw distant lightening, but according to the forecast the skies were due to clear in the next hour. Almost as soon as we reached the beach, the edge of the black cloud spat rain and the wind went dervish with the sand, blasting our bare legs. Families packed up furiously and we all dashed back to the parking lot like the end of the world was upon us. Defeated, Charlie and I retreated to a tiny beach he knew in ritzy Belvedere, Paradise Cove—right across the bay from San Quentin, where half the prisoners have tested positive for Covid, a fact I couldn’t get out of my head as we had our picnic on the beach. I must have appeared abstracted as I ate my egg salad sandwich, because Charlie asked me what was going on. When I explained that my head was filled with prisoners, Charlie said, “Maybe they’ll let the healthy ones out to fight fires for a dollar an hour.”

The edge of the black cloud spat rain and the wind

went dervish with the sand, blasting our bare legs.

Later, we swam; the water wasn’t too cold but it felt clammy, as the bay usually does. The day’s saving grace was the three-dozen Hog Island oysters that we picked up at Larkspur Landing, on the drive home. They were the sweetest I’ve had in a long time. What a bounty, heaped on an ancient Corona platter, with a fine mignonette that Charlie made, with sliced shallots soaked in champagne vinegar.

This morning the smoke in the air is bad, with a dusting of ash on the deck. We’re getting alerts of evacuations, a long distance from here, but it’s just beginning. Rolling blackouts are threatened, but we haven’t seen any yet. There are fires burning in Vacaville. Interstate 80 is closed between Vacaville and Fairfield. A huge ring of fire surrounds Lake Berryessa. The entire city of Healdsburg is ready to evacuate. From there, it burns north of the Russian River into West County, and nearly to the ocean.

We closed everything up last night to keep the bad air out. Charlie’s even thinking about turning on the old air conditioner. I told him I don’t mind the heat, but I think he’s worried about his parrot.

“Put a damp towel over his cage,” I suggested, “That’s how McTeague protected his canary when he was on the lam in Death Valley.”

“How did that turn out?” Charlie asked, knowing full well that both McTeague and the canary perished.

“Hey, this isn’t exactly Death Valley,” which was in the news last week for hitting a temperature of 130.

A little before noon I saw Charlie walk into the parrot room with a wet towel.

I had my first client via Zoom today: Aubrey Kincaid, a prodigious stutterer in his mid thirties. Aubrey wore a well-pressed Oxford cloth shirt for the occasion. I kept things simple in a sleeveless linen dress, with a red onyx pendant that Charlie gave me the night I moved in.

For some reason, I waved at my client. “How are you, Aubrey?”

“Good. Good,” he said, nodding.

“It’s nice seeing you. What a lovely shirt.”

Aubrey took an audible sniff of the air. “I just iron-ironed it. Sooooo,” he said, stretching the word out, a trick I taught him for gathering his composure, “I have-have been doing my exercises.”

“I can tell.” It was true. Aubrey spoke with more fluency than I remember. In the past he stammered over nearly every word and his head-jerks, which often accompanied his speech delays, had disappeared.

Aubrey worked as an accountant at a firm in Corte Madera and had gone through a dark period, losing clients he attributed to his stuttering. That’s why he’d started therapy in the first place, about six months before the pandemic hit. From what Aubrey told me, he’d been as traumatized by his childhood speech therapy as by the stuttering itself, so I took a very relaxed conversational approach to our sessions, mixing in a light exercise or two. I’d gotten Aubrey in the habit of reading aloud to himself everyday, and also exaggerating the head jerks that had become part of his stuttering routine; full awareness is the best path to elimination.

My goal for the first session was to have an easy conversation with Aubrey. That would allow me to do a proper evaluation after all the time’s that’s elapsed.

It delighted me that Aubrey kicked off the conversation. “Soooo, what’s new with you, Pa-pina?”

Aubrey had never managed to pronounce my name without some sort of a hitch and this time a guttural grunt followed his flub.

I carried on without pause. “I moved to Sonoma,” I said.

“I love Sa-sa-mona,” he said, leaving the damaged name alone, as I’d counseled, and continued: “I really like the town square. Have you been to The Girl and the Fig?” Aubrey beamed after saying so much without a problem.

“Yes, yes. It’s one of my favorite spots in town.”

“Me too. Soooo, Pa-pina, you look fine.”

Nice as it was to hear that I looked fine, Aubrey’s comment was inappropriate. I wondered if messing up my name had led him somewhere he hadn’t meant to go. In any case, after his head jerked hard right for the first time during our conversation, he carried on as if nothing odd had happened, which is pretty much the fate of a life-long stutterer—carrying on as well as one can.

Soooo, Pa-pina, you look fine.”

Nice as it was to hear that I looked fine,

Aubrey’s comment was inappropriate.

“I went out on a date,” he said.

“Oh, good.”

“It was kind of a disaster.”

“I’m sorry.”

“It wasn’t so much the sta-stutter-stuttering. I could deal with that. We met for coffee at an outside café. The young lady didn’t look like her photo. She was fa-fat. I, you know, I didn’t want to be rude, but I couldn’t think of any-any-anything to say.”

“But you hung in there.”

“Yep. I hung in there.” I could tell that Aubrey was studying his own reflection, mugging a bit for the camera.

“Good for you, Aubrey.”

“I also went to a Ba-ba-black Lives Matter protest in the city. Guess what,” he said and then chuckled. “My-my sign didn’t stutter.”

“What did it say?”

“No-no justice, no peace. I’m-I’m try-trying to get in touch with my-my privilege.”

“That’s great, Aubrey. Me too.”

He nodded his head proudly. “Except-cept, I don’t-don’t feel that privileged.” Aubrey then turned quiet. I could see the old shame spilling over him.

I carried on much of rest of the conversation, asking Aubrey about his job and his twin sisters who he’s worked hard to forgive after they teased him relentlessly throughout his stuttering childhood.

Aubrey chimed in with short answers and we agreed to Zoom the following Thursday.

I can’t get enough of Charlie lately. When I say that to myself, I think first of Charlie’s body and then of his soul. They both satisfy me. Which says a fuck of a lot. The funny thing is I’d rather not see Charlie much during the day. I’m at my desk trying to figure out how many clients I can work with under the circumstances. During the long pandemic months while I resisted the opportunity to work from a distance, I reinvented myself. I truly believe that. The hours of solitude, which frightened me at first, have now become a necessary feature of my daily life. I knew that moving in with Charlie would compromise my solitude to a degree, but I decided the trade-off was worth it.

During the recent hot days Charlie has come in to gawk at me, plotzed half naked in the executive swivel chair I commandeered from him. I don’t mind seeing him for a flash or having a quick lunch with him, but I prefer to save him until later, for love and play. We are still so new with each other that it’s premature to claim that familiarity breeds contempt, but perhaps I fear that if we are not rigorous about maintaining some distance contempt will develop.

I’m still puzzled that I could fall for a man who spends the bulk of his day training a parrot. I have no idea what he’s after, but he carries on like a mad scientist. He tries to keep the extent of his Roscoe training from me, claiming he’s in a rut, working on dead-end animation projects. I know better. Anyway, Charlie isn’t a dead-end kind of a guy. He has what’s described as the happiness gene; the dude is bubbling over with serotonin. It cheers me to be with a man, who’s neither cynical nor sarcastic, features of my nature that I’ve, at least temporarily, put on hold, but which thrived in the years I spent with my faux husband Vince. Does my choice of Charlie mean that I’ve evolved or does it portend an inevitable clash of natures that will destroy us? I’m inclined to believe the latter, but there’s no sense in counting my dead chickens before they croak.

I’m still puzzled that I could fall for a man

who spends the bulk of his day training a parrot.

The last two nights Charlie persuaded me to watch the Democratic convention. He gets tears in his eyes during all the human-interest stories, and when Obama made his marvelous speech the night before, Charlie clutched my hand. Last night the brave speech by the stuttering boy who met Joe Biden brought me to tears. I hesitate to believe this, but I think Charlie’s humanity is rubbing off on me.

One of the convention commentators mentioned that to help himself as a childhood stutterer, Biden read poems by W. B. Yeats.

“That’s the coolest thing I’ve ever heard about Biden—the dude stuttered his way through Yeats poems.”

“Have you ever used Yeats with your stutterers?” Charlie asked

“Not yet.” Then Charlie surprised me by reciting the first stanza of “The Second Coming”:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Hearing Charlie recite the lines moved me. “How did you memorize that?” I asked, foolishly.

“Oh, I’ve memorized a lot of poems. This one seems appallingly on point for the moment. It was written in 1919 at the end of World War I.”

“And, God damn,” I said, “I don’t know how a stutterer could get through that poem. Every other word is a trigger. Turning, widening anarchy, conviction, passionate.”

And then Charlie, who does not stutter, recited the entire poem not, as Vince does, with a lofty self-consciousness, but as a common man who wants to travel with the words and their meaning down the crooked road of his life.

WATCH a great gallery talk from American University, featuring these panelists:

Squeak Carnwath, Exhibition Curator

Cynthia de Bos, Director of Collections and Archives, Artists’ Legacy Foundation

Jack Rasmussen, AU Museum Director & Curator

Mark Van Proyen, Associate Professor of Painting at the San Francisco Art Institute, and exhibition catalog essayist

Unfortunately, the exhibition was cancelled due to Covid-19, but you can read American University’s exhibition catalog here.