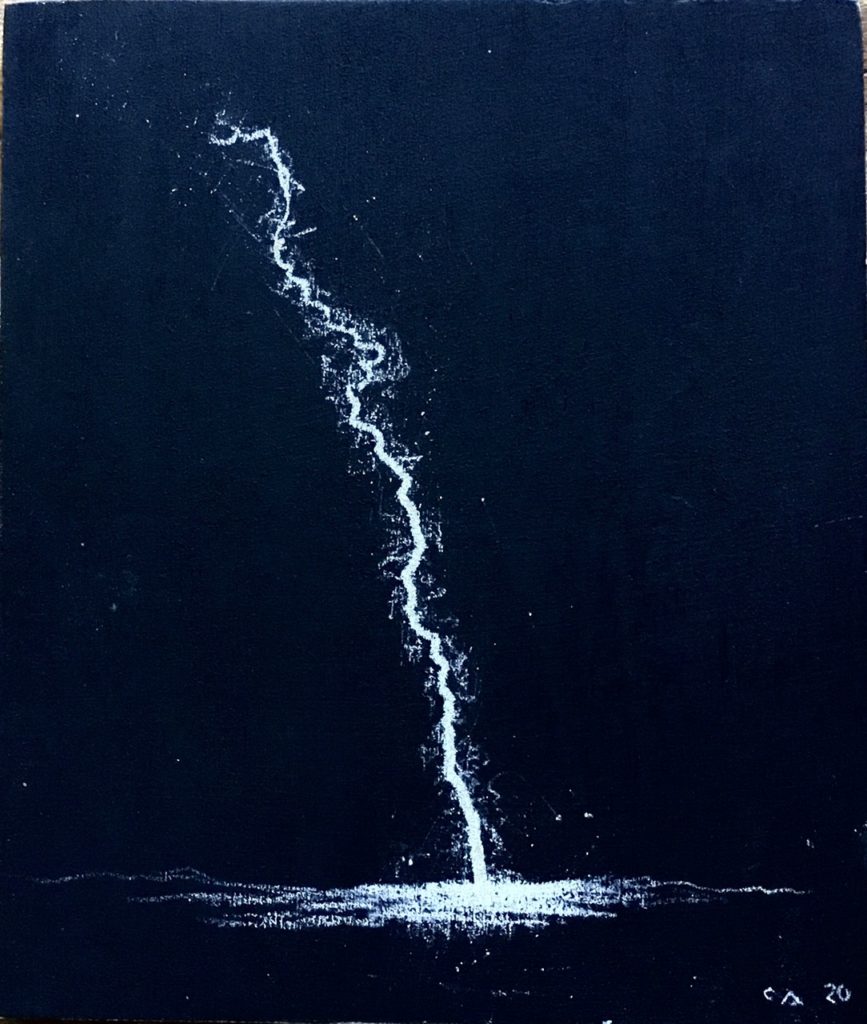

On Monday, Charlie and I took the morning off and headed to the ocean. The heat in Sonoma has been brutal, with the addition of something we rarely have: high humidity. We saw the pulses of dry lightening and heard thunder, the night before. The little bit it rained didn’t correspond with the lightening strikes, so numerous fires broke out.

We studied the skies as we approached Muir Beach on Monday. To our north, a stark black swath of sky was divided, by a line as hard as the horizon, from the mottled overcast sky above us. We guessed we were in the clear and lugged our blanket and cooler, filled with enough picnic fare for a big clan, onto the beach. We saw distant lightening, but according to the forecast the skies were due to clear in the next hour. Almost as soon as we reached the beach, the edge of the black cloud spat rain and the wind went dervish with the sand, blasting our bare legs. Families packed up furiously and we all dashed back to the parking lot like the end of the world was upon us. Defeated, Charlie and I retreated to a tiny beach he knew in ritzy Belvedere, Paradise Cove—right across the bay from San Quentin, where half the prisoners have tested positive for Covid, a fact I couldn’t get out of my head as we had our picnic on the beach. I must have appeared abstracted as I ate my egg salad sandwich, because Charlie asked me what was going on. When I explained that my head was filled with prisoners, Charlie said, “Maybe they’ll let the healthy ones out to fight fires for a dollar an hour.”

The edge of the black cloud spat rain and the wind

went dervish with the sand, blasting our bare legs.

Later, we swam; the water wasn’t too cold but it felt clammy, as the bay usually does. The day’s saving grace was the three-dozen Hog Island oysters that we picked up at Larkspur Landing, on the drive home. They were the sweetest I’ve had in a long time. What a bounty, heaped on an ancient Corona platter, with a fine mignonette that Charlie made, with sliced shallots soaked in champagne vinegar.

This morning the smoke in the air is bad, with a dusting of ash on the deck. We’re getting alerts of evacuations, a long distance from here, but it’s just beginning. Rolling blackouts are threatened, but we haven’t seen any yet. There are fires burning in Vacaville. Interstate 80 is closed between Vacaville and Fairfield. A huge ring of fire surrounds Lake Berryessa. The entire city of Healdsburg is ready to evacuate. From there, it burns north of the Russian River into West County, and nearly to the ocean.

We closed everything up last night to keep the bad air out. Charlie’s even thinking about turning on the old air conditioner. I told him I don’t mind the heat, but I think he’s worried about his parrot.

“Put a damp towel over his cage,” I suggested, “That’s how McTeague protected his canary when he was on the lam in Death Valley.”

“How did that turn out?” Charlie asked, knowing full well that both McTeague and the canary perished.

“Hey, this isn’t exactly Death Valley,” which was in the news last week for hitting a temperature of 130.

A little before noon I saw Charlie walk into the parrot room with a wet towel.

I had my first client via Zoom today: Aubrey Kincaid, a prodigious stutterer in his mid thirties. Aubrey wore a well-pressed Oxford cloth shirt for the occasion. I kept things simple in a sleeveless linen dress, with a red onyx pendant that Charlie gave me the night I moved in.

For some reason, I waved at my client. “How are you, Aubrey?”

“Good. Good,” he said, nodding.

“It’s nice seeing you. What a lovely shirt.”

Aubrey took an audible sniff of the air. “I just iron-ironed it. Sooooo,” he said, stretching the word out, a trick I taught him for gathering his composure, “I have-have been doing my exercises.”

“I can tell.” It was true. Aubrey spoke with more fluency than I remember. In the past he stammered over nearly every word and his head-jerks, which often accompanied his speech delays, had disappeared.

Aubrey worked as an accountant at a firm in Corte Madera and had gone through a dark period, losing clients he attributed to his stuttering. That’s why he’d started therapy in the first place, about six months before the pandemic hit. From what Aubrey told me, he’d been as traumatized by his childhood speech therapy as by the stuttering itself, so I took a very relaxed conversational approach to our sessions, mixing in a light exercise or two. I’d gotten Aubrey in the habit of reading aloud to himself everyday, and also exaggerating the head jerks that had become part of his stuttering routine; full awareness is the best path to elimination.

My goal for the first session was to have an easy conversation with Aubrey. That would allow me to do a proper evaluation after all the time’s that’s elapsed.

It delighted me that Aubrey kicked off the conversation. “Soooo, what’s new with you, Pa-pina?”

Aubrey had never managed to pronounce my name without some sort of a hitch and this time a guttural grunt followed his flub.

I carried on without pause. “I moved to Sonoma,” I said.

“I love Sa-sa-mona,” he said, leaving the damaged name alone, as I’d counseled, and continued: “I really like the town square. Have you been to The Girl and the Fig?” Aubrey beamed after saying so much without a problem.

“Yes, yes. It’s one of my favorite spots in town.”

“Me too. Soooo, Pa-pina, you look fine.”

Nice as it was to hear that I looked fine, Aubrey’s comment was inappropriate. I wondered if messing up my name had led him somewhere he hadn’t meant to go. In any case, after his head jerked hard right for the first time during our conversation, he carried on as if nothing odd had happened, which is pretty much the fate of a life-long stutterer—carrying on as well as one can.

Soooo, Pa-pina, you look fine.”

Nice as it was to hear that I looked fine,

Aubrey’s comment was inappropriate.

“I went out on a date,” he said.

“Oh, good.”

“It was kind of a disaster.”

“I’m sorry.”

“It wasn’t so much the sta-stutter-stuttering. I could deal with that. We met for coffee at an outside café. The young lady didn’t look like her photo. She was fa-fat. I, you know, I didn’t want to be rude, but I couldn’t think of any-any-anything to say.”

“But you hung in there.”

“Yep. I hung in there.” I could tell that Aubrey was studying his own reflection, mugging a bit for the camera.

“Good for you, Aubrey.”

“I also went to a Ba-ba-black Lives Matter protest in the city. Guess what,” he said and then chuckled. “My-my sign didn’t stutter.”

“What did it say?”

“No-no justice, no peace. I’m-I’m try-trying to get in touch with my-my privilege.”

“That’s great, Aubrey. Me too.”

He nodded his head proudly. “Except-cept, I don’t-don’t feel that privileged.” Aubrey then turned quiet. I could see the old shame spilling over him.

I carried on much of rest of the conversation, asking Aubrey about his job and his twin sisters who he’s worked hard to forgive after they teased him relentlessly throughout his stuttering childhood.

Aubrey chimed in with short answers and we agreed to Zoom the following Thursday.

I can’t get enough of Charlie lately. When I say that to myself, I think first of Charlie’s body and then of his soul. They both satisfy me. Which says a fuck of a lot. The funny thing is I’d rather not see Charlie much during the day. I’m at my desk trying to figure out how many clients I can work with under the circumstances. During the long pandemic months while I resisted the opportunity to work from a distance, I reinvented myself. I truly believe that. The hours of solitude, which frightened me at first, have now become a necessary feature of my daily life. I knew that moving in with Charlie would compromise my solitude to a degree, but I decided the trade-off was worth it.

During the recent hot days Charlie has come in to gawk at me, plotzed half naked in the executive swivel chair I commandeered from him. I don’t mind seeing him for a flash or having a quick lunch with him, but I prefer to save him until later, for love and play. We are still so new with each other that it’s premature to claim that familiarity breeds contempt, but perhaps I fear that if we are not rigorous about maintaining some distance contempt will develop.

I’m still puzzled that I could fall for a man who spends the bulk of his day training a parrot. I have no idea what he’s after, but he carries on like a mad scientist. He tries to keep the extent of his Roscoe training from me, claiming he’s in a rut, working on dead-end animation projects. I know better. Anyway, Charlie isn’t a dead-end kind of a guy. He has what’s described as the happiness gene; the dude is bubbling over with serotonin. It cheers me to be with a man, who’s neither cynical nor sarcastic, features of my nature that I’ve, at least temporarily, put on hold, but which thrived in the years I spent with my faux husband Vince. Does my choice of Charlie mean that I’ve evolved or does it portend an inevitable clash of natures that will destroy us? I’m inclined to believe the latter, but there’s no sense in counting my dead chickens before they croak.

I’m still puzzled that I could fall for a man

who spends the bulk of his day training a parrot.

The last two nights Charlie persuaded me to watch the Democratic convention. He gets tears in his eyes during all the human-interest stories, and when Obama made his marvelous speech the night before, Charlie clutched my hand. Last night the brave speech by the stuttering boy who met Joe Biden brought me to tears. I hesitate to believe this, but I think Charlie’s humanity is rubbing off on me.

One of the convention commentators mentioned that to help himself as a childhood stutterer, Biden read poems by W. B. Yeats.

“That’s the coolest thing I’ve ever heard about Biden—the dude stuttered his way through Yeats poems.”

“Have you ever used Yeats with your stutterers?” Charlie asked

“Not yet.” Then Charlie surprised me by reciting the first stanza of “The Second Coming”:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Hearing Charlie recite the lines moved me. “How did you memorize that?” I asked, foolishly.

“Oh, I’ve memorized a lot of poems. This one seems appallingly on point for the moment. It was written in 1919 at the end of World War I.”

“And, God damn,” I said, “I don’t know how a stutterer could get through that poem. Every other word is a trigger. Turning, widening anarchy, conviction, passionate.”

And then Charlie, who does not stutter, recited the entire poem not, as Vince does, with a lofty self-consciousness, but as a common man who wants to travel with the words and their meaning down the crooked road of his life.